|

Size: 13032

Comment:

|

Size: 14971

Comment:

|

| Deletions are marked like this. | Additions are marked like this. |

| Line 38: | Line 38: |

| apogee velocity: $ ~ \large v_a ~=~ v_0 ( 1 - {\epsilon} ) ~~~~~~~~ $ perigee velocity: $ ~ \large v_p ~=~ v_0 ( 1 + {\epsilon} ) $ | apogee velocity: $ ~ \large v_a ~=~ v_0 ( 1 - {\epsilon} ) ~~~~~~~~ $ perigee velocity: $ ~ \large v_p ~=~ v_0 ( 1 + {\epsilon} ) $ |

| Line 58: | Line 58: |

| The atmosphere becomes exponentially thinner with altitude until it is as low as the density of interplanetary space. The density can be approximated by | The atmosphere becomes exponentially thinner with altitude until it is as low as the density of interplanetary space. The density can be approximated by |

| Line 60: | Line 60: |

| $ \large \rho ( r ) ~ = ~ \rho (r) ~ e^{ - ( r - r_0 ) / H } $ | $ \large \rho ( r ) ~ = ~ \rho (r) ~ e^{ - ( r - r_0 ) / H } $ |

| Line 62: | Line 62: |

| where $ {\rho}_0 $ is the density at altitude $ r_0 $, a function of temperature, solar activity, and longitude, which vary with time. $ H $ is the scale height, the distance over which the atmosphere density decays by a factor of e = 2.718 . Solar activity can triple temperature, and greatly increase the density of the atmosphere at very high altitude. Most of the gas at these high altitudes is hydrogen and helium. Because the sun heats the atmosphere during the day, the temperature and density peaks in the afternoon 1400 hours position. The air is coldest at before dawn, at the 0400 hours position. The mean free path of the air molecules above 1000 km is larger than the scale height, so the atoms rarely collide. | where $ {\rho}_0 $ is the density at altitude $ r_0 $, a function of temperature, solar activity, and longitude, which vary with time. $ H $ is the scale height, the distance over which the atmosphere density decays by a factor of e = 2.718 . Solar activity can triple temperature, and greatly increase the density of the atmosphere at very high altitude. Most of the gas at these high altitudes is hydrogen and helium. Because the sun heats the atmosphere during the day, the temperature and density peaks in the afternoon 1400 hours position. The air is coldest at before dawn, at the 0400 hours position. The mean free path of the air molecules above 1000 km is larger than the scale height, so the atoms rarely collide. |

| Line 68: | Line 68: |

| A small change in radius makes a large change in drag, and the velocity is inversely proportional to radius. We will assume the velocity near perigee is a constant $ v_p $. So, the drag force for area $ A $ (the area perpendicular to the velocity) is | A small change in radius makes a large change in drag, and the velocity is inversely proportional to radius. We will assume the velocity near perigee is a constant $ v_p $. So, the drag force for area $ A $ (the area perpendicular to the velocity) is |

| Line 86: | Line 86: |

| $ v_0 = v_p / ( 1 + \epsilon ) $ | $ v_0 = v_p / ( 1 + \epsilon ) $ |

| Line 88: | Line 88: |

| $ \large v_r ~ = ~ { \Large \epsilon \over { ( 1 + \epsilon ) } } v_p \theta ~ ~ ~ ~ $ radial velocity near perigee for small $ \theta $ | $ \large v_r ~ = ~ { \Large \epsilon \over { ( 1 + \epsilon ) } } v_p \theta ~ ~ ~ ~ $ radial velocity near perigee for small $ \theta $ |

| Line 92: | Line 92: |

| Define $ y = r - r_p $ | Define $ y = r - r_p $ |

| Line 106: | Line 106: |

| derivative: $ \large dt ~ \approx ~ { \Large \sqrt{ \left( 1 + { 1 \over \epsilon } \right) { { r_p } \over { {v_p}^2 y } } } } ~ ~ dy $ | derivative: $ \large dt ~ \approx ~ { \Large \sqrt{ \left( 1 + { 1 \over \epsilon } \right) { { r_p } \over { {v_p}^2 y } } } } ~ ~ dy $ |

| Line 116: | Line 116: |

| $ \large \Delta v_p ~ = ~ { \LARGE \int_0^{\infty} } { { \rho(r_p) A } \over M } {v_p}^2 e^{-y / H } ~ { \sqrt{ \left( 1 + { 1 \over \epsilon } \right) { { r_p } \over {v_p}^2 y } } } \large ~ dy $ |

$ \large \Delta v_p ~ = ~ { \LARGE \int_0^{\infty} } { { \rho(r_p) A } \over M } {v_p}^2 e^{-y / H } ~ { \sqrt{ \left( 1 + { 1 \over \epsilon } \right) { { r_p } \over {v_p}^2 y } } } \large ~ dy $ |

| Line 120: | Line 120: |

| $ \large \Delta v_p ~ = ~ { { \rho (r_p) ~ A ~ v_p } \over M } \sqrt{\left( 1 + { 1 \over \epsilon } \right) r_p } { \LARGE \int_0^{\infty} } e^{-y / H } \sqrt{ 1 / y } ~ dy ~ ~ ~ $ | $ \large \Delta v_p ~ = ~ { { \rho (r_p) ~ A ~ v_p } \over M } \sqrt{\left( 1 + { 1 \over \epsilon } \right) r_p } { \LARGE \int_0^{\infty} } e^{-y / H } \sqrt{ 1 / y } ~ dy ~ ~ ~ $ |

| Line 141: | Line 141: |

| ''' Equation S4:''' $ \large v_{pt} ~=~ \Large \sqrt{ { {2 \mu} \over {r_p} } - { \mu \over {r_p + H } } } $ | ''' Equation S4:''' $ \large v_{pt} ~=~ \Large \sqrt{ { {2 \mu} \over {r_p} } - { \mu \over {r_p + H } } } $ |

| Line 155: | Line 155: |

| '''specific energy:''' $ \large E = { { - \mu } \over { 2 r } } $ | '''specific energy:''' $ \large E = { { - \mu } \over { 2 r } } ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ \large { {d E} \over {d r} } = { \mu \over { 2 r^2 } } ~~~~~~~~~ \large { {d r} \over {d E} } = { { 2 r^2 } \over \mu } $ |

| Line 157: | Line 157: |

| $ \large { {d E} \over {d r} } = { \mu \over { 2 r^2 } } ~~~~~~~~~ \large { {d r} \over {d E} } = { { 2 r^2 } \over \mu } $ | $ \Large { {d E} \over {d t} } {\large = - a v = } { { - \rho(r) A v^3 } \over { 2 M } } ~ = { { - \rho(r) } \over 2 } { A \over M } \left( \mu \over r \right)^{3/2} $ |

| Line 159: | Line 159: |

| $ \Large { {d E} \over {d t} } {\large = - a v = } { { - \rho(r) A v^3 } \over { 2 M } } ~ = { { - \rho(r) } \over 2 } { A \over M } \left( \mu \over r \right)^{3/2} $ $ \large { {d r} \over {d t} } = { {d E} \over {d t} } { {d r} \over {d E} } = { { - \rho(r) } \over 2 } { A \over M } \left( \mu \over r \right)^{3/2} { { 2 r^2 } \over \mu } = - \rho (r) { A \over M } \sqrt{ \mu r } ~ $ |

$ \large { {d r} \over {d t} } = { {d E} \over {d t} } { {d r} \over {d E} } = { { - \rho(r) } \over 2 } { A \over M } \left( \mu \over r \right)^{3/2} { { 2 r^2 } \over \mu } = - \rho (r) { A \over M } \sqrt{ \mu r } ~ $ |

| Line 165: | Line 163: |

| MoreLater | === Computer Models and Graphs === We will use the nrlmsise-00 atmosphere model and this program: * [[ attachment:makefile | makefile ]] * [[ attachment:exp02.c | exp02.c ]] * [[ attachment:exp02.dat | exp02.dat ]] * [[ attachment:exp02.gp | exp02.gp ]] * [[ attachment:nrlmsise-00.c | nrlmsise-00.c ]] * [[ attachment:nrlmsise-00_data.c | nrlmsise-00_data.c ]] * [[ attachment:nrlmsise-00.h | nrlmsise-00.h ]] To make these plots: ||{{attachment:exp.png | |width=512}}||[[attachment:exp.png |exp.png ]]|| ||{{attachment:decay.png| |width=512}}||[[attachment:decay.png|decay.png]]|| ||{{attachment:vdrop.png| |width=512}}||[[attachment:vdrop.png|vdrop.png]]|| === Avoiding ISS === {{ attachment:OrbitHeightPlot.aspx.png | | width=512 }} [[ attachment:OrbitHeightPlot.aspx.png | ISS altitude over time ]] The International Space Station is in a 51.6° inclination orbit, crossing the equator twice per $ T $ = 5570 second orbit at an altitude ranging from 400 km to 420 km. Thinsats are small and light - nevertheless, we should minimize the chances of hitting it, so our experimental perigee should be above 450 kilometers or so, and the decay rate through the ISS altitude should be fast. Assuming a launch from India's Satish Dhawan or the ESS Kourou launch sites, the experimental orbit will be close to equatorial. Closing velocity will be the orbital velocity 7.66 km/s times sin(51.6°) or 6 km/s . The orbit circumference $ C $ is 42650 kilometers. The ISS solar panels are 2500 m^2^, assume the whole station area is $ A $ = 10000 m^2^. For $ N $ (est 200 ) pointlike thinsats descending at velocity $ V $ ( 0.1 m/s at solar minimum, 1.0 m/s at solar maximum ), the chance of one collision $ P $ is $ \large P = N { { 2 A } \over { C T V } } = 200 * 2 * 10000 / ( 42650000 * 5570 * 7660 ) = 2E-9 $ |

Hitchhiker Server Sky Test

Testing the first server sky thinsat arrays may be challenging - they don't belong in a common orbit, they won't last long below 1000 km altitude due to ram drag. It would be nice to deploy the first tests at M288, but that will require a custom launch.

Instead, let's dispense as a co-payload from a GTO transfer orbit. We will test in a highly inclined orbit, in three steps:

1) Deploy: use a cold gas thruster to slightly lower apogee and significantly raise perigee. This will be the orbit for our experiment. The inclination of this orbit will be a function of launch latitude, and the ascending node will be on the equatorial plane.

2) Dispense approximately 100 thinsats near apogee. The subsequent fate of the dispenser is undefined; perhaps we can use it later for collision experiments.

3) Experiment: the thinsats maneuver into arrays and begin the test. The perigee drag is high enough that the apogee will decay significantly with each orbit. Thinsats will orient for minimum drag, but because they are curved the drag will be significant.

4) Deorbit: if damage has not set the thinsats tumbling, lock the optical thrusters to produce a rapid yaw tumble. This will greatly increase perigee drag.

5) Reentry: after apogee decays to perigee, the orbit will rapidly spiral in. When tumbling thinsats reach ISS altitude, they will reenter one or two orbits later.

The starting GTO transfer orbit will have a perigee radius of r_{P-GTO} (perhaps 7000 km) and an apogee radius of r_{A-GTO} (perhaps 42,100 km ) one or two orbits after release from the GTO upper stage. Using these numbers and the gravitational coefficient \mu , we can compute the perigee and apogee velocities v_{P-GTO} and p_{A-GTO} , the semimajor axis a , the eccentricity \epsilon , and the characteristic velocity v_0 .

Computing the experimental orbits will require numerical integration, with estimated perturbations telling us how difficult it will be to keep arrays together. We can approximate all thinsats in an array in one trajectory in two regimes: (1) highly elliptical, dominated by perigee drag on a thinsat oriented for minimum drag, and (2) a spiral, with decay increasing rapidly as thermospheric density increases exponentially and the thinsats tumble. It may be possible to arrange and observe a collision between one or two thinsats and the heavier and slow-orbit-decay dispenser, which will still be in a high velocity, high eccentricity orbit.

Gas density will low during quiet sun periods around 2016, and maximum about 5 years later in 2021. If possible, we should schedule the test so that all probably-disabled thinsats will reenter during that solar maximum.

Computing the Experimental orbit

The initial orbit

Starting with r_{A-GTO} and r_{P-GTO} , we can compute the semimajor axis a and other parameters:

\large a ~=~ 0.5 * ( r_{A-GTO} + r_{P-GTO} ) ~~~~~~~ semimajor axis

\large \epsilon ~ = ~ ( r_{A-GTO} - r_{P-GTO} ) / ( r_{A-GTO} + r_{P-GTO} ~~~~~ eccentricity

\large T ~=~ 2\pi \sqrt{ a^3/\mu } ~~~~~ orbital period (sidereal)

\large v_0 ~=~ \sqrt{ \mu / ( a (1 - {\epsilon}^2) ) } ~~~~~ characteristic velocity

apogee velocity: ~ \large v_a ~=~ v_0 ( 1 - {\epsilon} ) ~~~~~~~~ perigee velocity: ~ \large v_p ~=~ v_0 ( 1 + {\epsilon} )

For the first approximation, ignore J_2 and other complexities in the gravitational field, but include them in the numerical model. They will cause the elliptical orbit to precess towards the east.

Find \epsilon , a , and T from r_p , v_p and the constant \mu :

\large r_p ~=~ ( 1 - \epsilon ) a ~~~~~~~~ \large ( 1 - \epsilon ) ~=~ \Large { r_p \over a } ~~~

\large v_p ~=~ \LARGE \sqrt{{{2\mu}\over{r_p}}-{{\mu}\over{a}}} ~~~~~~~~ \Large { v_p^2 \over \mu } ~=~ { 2 \over r_p } - { 1 \over a } ~~~~~~~~ \Large { 1 \over a } ~=~ { 2 \over r_p } - { v_p^2 \over \mu } ~~~~~~~~ { r_p \over a } ~=~ 2 - { { r_p v_p^2 } \over \mu } ~~~~~~~~ \large ( 1 - \epsilon ) ~=~ 2 - \Large { { r_p v_p^2 } \over \mu }

Atmospheric Drag

The atmosphere becomes exponentially thinner with altitude until it is as low as the density of interplanetary space. The density can be approximated by

\large \rho ( r ) ~ = ~ \rho (r) ~ e^{ - ( r - r_0 ) / H }

where {\rho}_0 is the density at altitude r_0 , a function of temperature, solar activity, and longitude, which vary with time. H is the scale height, the distance over which the atmosphere density decays by a factor of e = 2.718 . Solar activity can triple temperature, and greatly increase the density of the atmosphere at very high altitude. Most of the gas at these high altitudes is hydrogen and helium. Because the sun heats the atmosphere during the day, the temperature and density peaks in the afternoon 1400 hours position. The air is coldest at before dawn, at the 0400 hours position. The mean free path of the air molecules above 1000 km is larger than the scale height, so the atoms rarely collide.

When an object passes through this thin gas at very high orbital speeds, it collides with the gas molecules, and experiences a force proportional to the gas density \rho times the area A times the velocity squared . The gas is thickest at perigee, a density of \rho (r_p) , where the scale height (which increases with altitude) is H_p . The modified density equation is:

\large \rho ( r ) ~ = ~ \rho (r_p) ~ e^{ - ( r - r_p ) / H(r_p) } ~ ~ ~ ~ density near perigee

A small change in radius makes a large change in drag, and the velocity is inversely proportional to radius. We will assume the velocity near perigee is a constant v_p . So, the drag force for area A (the area perpendicular to the velocity) is

\large F ~ = ~ {1\over 2} \rho (r) A { v_p}^2 ~ ~ ~ ~ drag force

The acceleration for a thinsat with mass M is:

\large acc ~ = ~{ \Large { \rho (r) A } \over { 2 M } } { v_p}^2 ~ ~ ~ ~ acceleration

Experiment and Deorbit : Decaying Orbit from Elliptical to Circular

Assuming about 1 cm of curvature on 20 cm wide thinsat, and a noontime or midnight perigee, the drag area is about 15 cm2 or 1.5e-3 m2. During intentional deorbiting, a thinsat is tumbled around an axis perpendicular to the orbit, increasing drag area to 160 cm2 or 1.6e-2 m2. Intentional deorbiting after the experiment is complete will reduce the time in orbit and potential space debris hazards to other satellites.

When r_a - r_p is much greater than the scale height H_p , we can crudely approximate the orbital decay as if it all occurs near perigee.

The radial velocity v_r is zero at perigee, and increases in magnitude at angles to the side:

\large v_r ~ \approx ~ \epsilon v_0 \sin( \theta ) ~ ~ ~ ~ radial velocity at orbit angle \theta

v_0 = v_p / ( 1 + \epsilon )

\large v_r ~ = ~ { \Large \epsilon \over { ( 1 + \epsilon ) } } v_p \theta ~ ~ ~ ~ radial velocity near perigee for small \theta

\Large { { d \theta } \over { d t } } ~ \large \approx ~ \Large { { v_p } \over { r_p } } ~ ~ ~ ~ angular velocity near perigee

Define y = r - r_p

\Large { dy \over dt } \large ~ = ~ \Large { dr \over dt } \large ~ = ~ v_r \approx ~ { \Large \epsilon \over { ( 1 + \epsilon ) } } v_p \theta ~ ~ ~ ~ radial velocity

Assuming angular velocity is approximately constant, and starting with t = 0 at perigee:

\theta ~ \approx ~ { v_p \over r_p } t

so \Large { dy \over dt } \large ~ \approx ~ { \Large \epsilon \over { ( 1 + \epsilon ) } } { {v_p}^2 \over { r_p } } ~ t

Integrating: \large y ~ \approx ~ { \Large \epsilon \over { 2 ( 1 + \epsilon ) } } { {v_p}^2 \over { r_p } } ~ t^2

Solving for t as a function of y: ~~~ \large t ~ \approx ~ { \Large \sqrt{ { { 2 ( 1 + \epsilon ) } \over \epsilon } ~ { { r_p } \over {v_p}^2 } ~ \large y } }

derivative: \large dt ~ \approx ~ { \Large \sqrt{ \left( 1 + { 1 \over \epsilon } \right) { { r_p } \over { {v_p}^2 y } } } } ~ ~ dy

The decrease of v_p during one perigee pass is the integral of the acceleration over time :

\large \Delta v_p ~ = ~ { \LARGE \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} } acc ~ dt ~ ~ ~ ~ Equation S0

From symmetry: \large \Delta v_p ~ = ~ 2 { \LARGE \int_0^{\infty} } acc ~ dt ~ = ~ 2 { \LARGE \int_0^{\infty} } { { \rho(r_p) A } \over { 2 M } } {v_p}^2 e^{-y / H } \large ~ dt

Recasting as an integral over y:

\large \Delta v_p ~ = ~ { \LARGE \int_0^{\infty} } { { \rho(r_p) A } \over M } {v_p}^2 e^{-y / H } ~ { \sqrt{ \left( 1 + { 1 \over \epsilon } \right) { { r_p } \over {v_p}^2 y } } } \large ~ dy

Moving and combining constants out of the integral:

\large \Delta v_p ~ = ~ { { \rho (r_p) ~ A ~ v_p } \over M } \sqrt{\left( 1 + { 1 \over \epsilon } \right) r_p } { \LARGE \int_0^{\infty} } e^{-y / H } \sqrt{ 1 / y } ~ dy ~ ~ ~

The integral can be solved with a change in variables, let ~ y = H b^2 ~ so that ~ dy = 2 H b ~ db ~ and ~~~ \sqrt{ 1 / y } ~~ dy ~ = ~ 2 \sqrt{ H } ~~ db

{ \LARGE \int_0^{\infty} } e^{-y / H } \sqrt{ 1 / y } ~ dy ~ = ~ 2 \sqrt{ H } { \LARGE \int_0^{\infty} } e^{-b^2} ~ db ~ = ~ 2 \sqrt{ H } \sqrt{ \pi }/ 2 ~ = ~ \sqrt{ \pi H } ~~~

\large \Delta v_p ~ = ~ { { \rho (r_p) ~ A ~ v_p } \over M } \sqrt{ \left( 1 + { 1 \over \epsilon } \right) \pi ~ r_p ~ H } ~~~ Equation S1

resulting in:

Equation S3: \large \Delta v_p = \Large { { \rho (r_p) ~ A ~ v_p } \over M } \sqrt{ { \pi ~ r_p ~ H } \over { 1 - \mu / r_p v_p^2 } } ~~~ Apogee Radius: \large r_a = \Large { r_p \over { 1 - { { 2 \mu } \over { r_p { v_p }^2 } } } } ~~~ Orbit Period: \large T = \Large { 2 \pi \mu \left( r_p \over { 2 \mu - r_p { v_p }^2 } \right)^{3/2} }

Solve equation S3 repeatedly, decrementing v_p , until the apogee drops below a threshold and the assumptions become invalid. If the eccentricity drops to zero (circular orbit at r_p = r_a ) the eccentricity drops to 0, as does the denominator of the square root, and \Delta v_p goes asymptotic.

We will arbitrarily assume this happens when r_a - r_p = 2 H , that is, below a velocity threshold v_{pt} :

\large a_t ~=~ r_p + H ~~~ semimajor axis at threshold

Equation S4: \large v_{pt} ~=~ \Large \sqrt{ { {2 \mu} \over {r_p} } - { \mu \over {r_p + H } } }

If v_p < v_{p-TH} , the orbit has decayed to a circular orbit, the experimental and deorbit phases are over, and it is time to begin the re-entry phase, to clean the debris of our experiment out of orbit. By tumbling the thinsats to begin accelerated deorbiting, the effective area A is increased.

Re-Entry: Decaying Circular Orbit

In this phase, we begin with r_p = r_a = r_{p-EXP} or experimental perigee radius, v_p = v_a = \sqrt{ \mu / r_{p-EXP} } , circular orbital velocity at that experimental perigee radius. Atmospheric density is not symmetric with longitude, with maximum density occuring 2 hours after noon and minumum density occuring 4 hours after midnight, the average density is sufficient to estimate re-entry time though not the exact trajectory. Assume that the mean free path is longer than the width of the thinsat - this is true down to 110 km altitude.

Drag acceleration reduces energy, which lowers the orbit. Solving for dr / dt :

acceleration: ~ \large a = { \Large { \rho(r) A } \over { 2 M } } v^2 ~~~~~~ velocity: \large v = \Large \sqrt{ \mu \over r }

specific energy: \large E = { { - \mu } \over { 2 r } } ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ \large { {d E} \over {d r} } = { \mu \over { 2 r^2 } } ~~~~~~~~~ \large { {d r} \over {d E} } = { { 2 r^2 } \over \mu }

\Large { {d E} \over {d t} } {\large = - a v = } { { - \rho(r) A v^3 } \over { 2 M } } ~ = { { - \rho(r) } \over 2 } { A \over M } \left( \mu \over r \right)^{3/2}

\large { {d r} \over {d t} } = { {d E} \over {d t} } { {d r} \over {d E} } = { { - \rho(r) } \over 2 } { A \over M } \left( \mu \over r \right)^{3/2} { { 2 r^2 } \over \mu } = - \rho (r) { A \over M } \sqrt{ \mu r } ~

Equation S5: \large d t = { -1 \over { \rho(r) \LARGE { A \over M } \sqrt{ \mu r } } } ~ d r

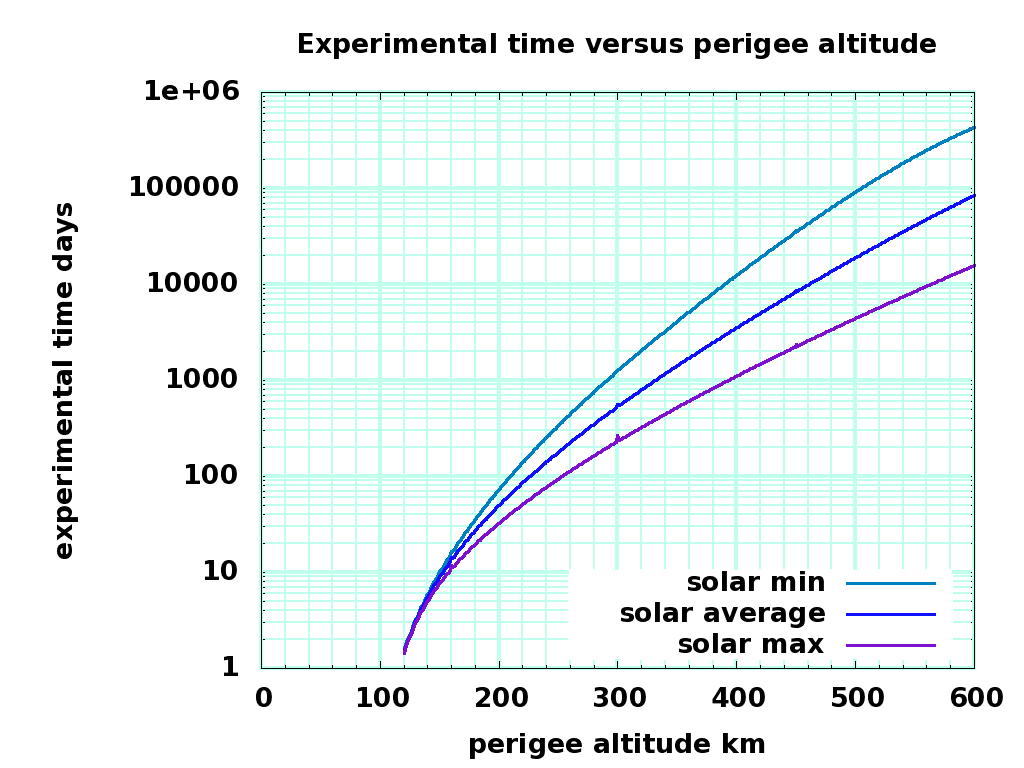

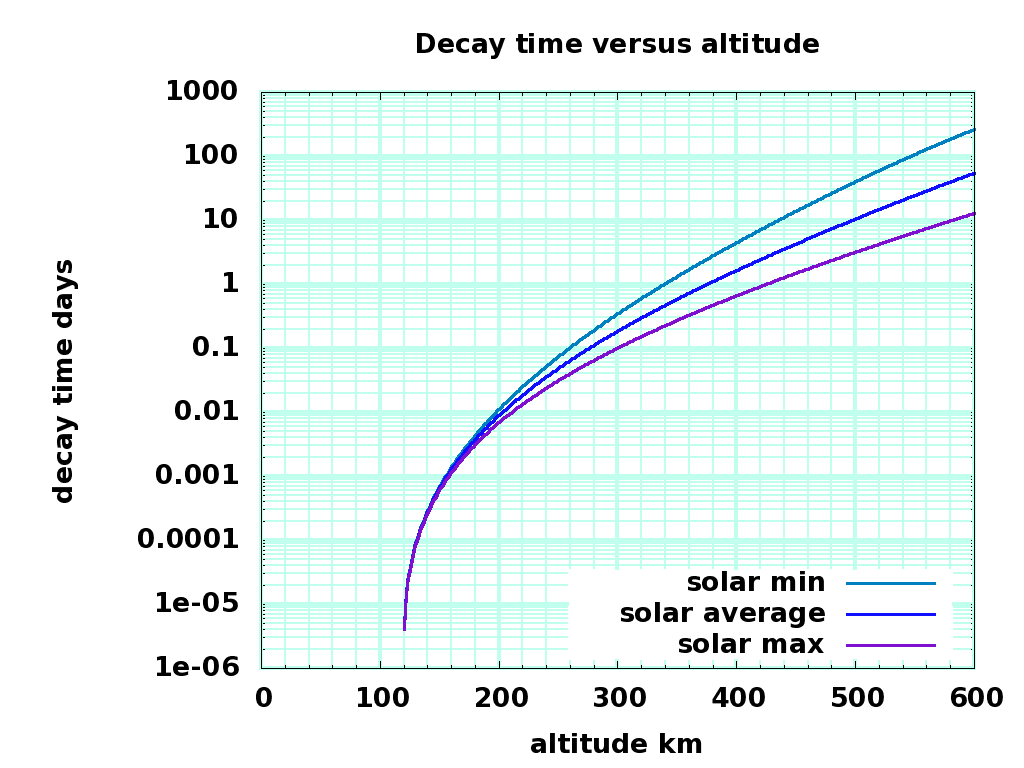

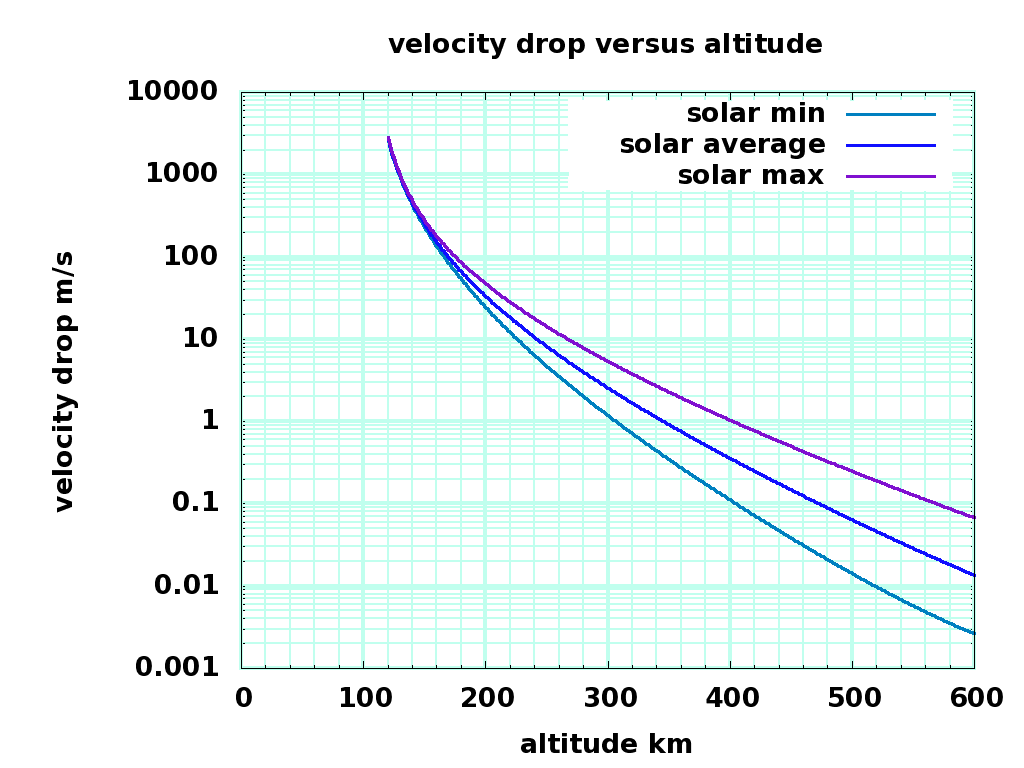

Computer Models and Graphs

We will use the nrlmsise-00 atmosphere model and this program:

To make these plots:

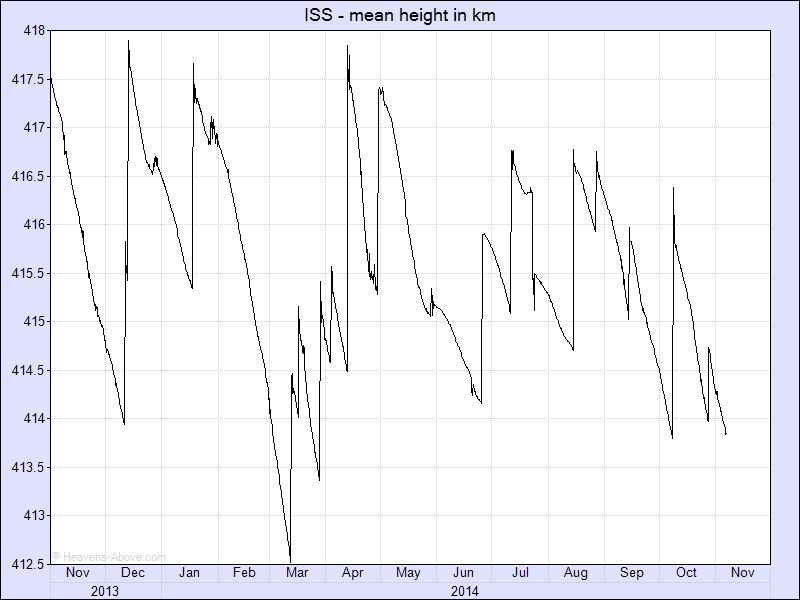

Avoiding ISS

The International Space Station is in a 51.6° inclination orbit, crossing the equator twice per T = 5570 second orbit at an altitude ranging from 400 km to 420 km. Thinsats are small and light - nevertheless, we should minimize the chances of hitting it, so our experimental perigee should be above 450 kilometers or so, and the decay rate through the ISS altitude should be fast. Assuming a launch from India's Satish Dhawan or the ESS Kourou launch sites, the experimental orbit will be close to equatorial. Closing velocity will be the orbital velocity 7.66 km/s times sin(51.6°) or 6 km/s . The orbit circumference C is 42650 kilometers. The ISS solar panels are 2500 m2, assume the whole station area is A = 10000 m2. For N (est 200 ) pointlike thinsats descending at velocity V ( 0.1 m/s at solar minimum, 1.0 m/s at solar maximum ), the chance of one collision P is

\large P = N { { 2 A } \over { C T V } } = 200 * 2 * 10000 / ( 42650000 * 5570 * 7660 ) = 2E-9