|

Size: 7189

Comment: added hydrogen ballast shell, dyson reference

|

Size: 7911

Comment:

|

| Deletions are marked like this. | Additions are marked like this. |

| Line 30: | Line 30: |

| And what would we do with such a shell? Perhaps some form of DigitalImmortality. |

|

| Line 32: | Line 34: |

| An even colder shell would provide far more computation per watt of sunlight - the energy per bit could be reduced. However, reducing the temperature by 4x (to 14K) would require 256x the area and 16x the distance, and there is not enough carbon in the solar system to do that without some form of ballast. However, 14K is cold enough to freeze hydrogen, and that could become the ballast, perhaps frozen into lenses on the front surface of the thinsats, with the carbon concentrated at the foci. The resulting computation would be slower and more widely dispersed, but more powerful overall. Such a system could move further and further out, consuming more and more of the hydrogen in the solar system, and the shells would become increasingly hard to detect against the 2.7K cosmic background. Perhaps that is what the "dark matter" actually is; while Brownlee and Ward's "Rare Earth" teaches us that advanced civilizations are incredibly rare, perhaps one per several galaxies, in a few billion years only a few advanced civilizations may engulf most of the stars in large clusters of galaxies, leading to large voids in the sky. | An even colder shell could provide more computation per watt of sunlight, because the energy per bit could be reduced. Reducing the temperature by 4x (to 14K) would require 256x the area and 16x the distance, and there is not enough carbon in the solar system to do that without some form of ballast. However, 14K is cold enough to freeze hydrogen, and that could become the ballast, perhaps frozen into lenses on the front surface of the thinsats, with the carbon concentrated at the foci. The resulting computation would be slower and more widely dispersed, but more powerful overall. Such a system could move further and further out, consuming more and more of the hydrogen in the solar system, and the shells would become increasingly hard to detect against the 2.7K cosmic background. |

| Line 34: | Line 36: |

| == Reference == | Perhaps that is what some "dark matter" actually is. Brownlee and Ward's "Rare Earth" teaches us that advanced civilizations are probably incredibly rare, perhaps one per several galaxies. However, in a few billion years, a few advanced civilizations may engulf most of the stars in large clusters of nearby galaxies, leading to large voids in the sky and anomalously high mass to light ratios. These large spheres would occult stars (though not galaxies) behind them; a very high resolution space telescope capable of observing individual stars billions of light years away, millions of stars, might detect a few these decade-long occultations. == Solar heating over time == {{attachment:solar_Gyear.png}} The balance of light to mass holds the thinsat shell in place. As the sun ages, irradiation increases. This can be accommodated by adding mass to the thinsats, or by making them smaller and thicker, letting some light (and heat) escape through gaps. == References == |

Server Sky to Dyson Shell

The following is extremely speculative. The intent is not to outline What Must Happen, but to estimate upper bounds for Server Sky.

Freeman Dyson once proposed that advanced civilizations could be identified by their infrared emissions. Eventually, they would capture all the light from their stars, and turn the power into heat. The mechanism was unspecified, but would be a material shell surrounding the star. NOT a solid sphere; Dyson proposed (see reference below) something more like a layer of myriads of orbiting objects.

Light is very low entropy energy. Black body heat is high entropy energy. A very high efficiency computer would capture optical photons from the sun, between 1eV and 4eV, use the energy for processing, and emit 2.7K black body infrared photons, a spectrum centering around 240 microelectron volts. However, such a shell would be light-years across; anything closer will be warmer.

The lightest possible thin satellite will have zero orbital velocity, and hover in a balance between light pressure and solar gravity. This balance is the same throughout the solar system - both the light pressure and the gravity drop off as the inverse square. At the orbital radius of the Earth, the solar illumination is 1366 watts per meter squared, producing light pressure of P/c = 4.6 microPascal . The solar gravitational acceleration is 5.93 mm/s2. So the mass per unit area is the pressure divided by the acceleration, or about 0.75 grams per meter squared.

For a complete shell, though, this will be modified by infrared heat emission and absorption. The shell has a temperature, at equilibrium when the outbound infrared flux equals the inbound light flux. Assuming inner and outer black body surfaces with an emissivity of 1, then heat flux emitted inbound, and the flux absorbed from the rest of the inside of the shell, equals the emitted heat flux (and the light flux). The internal emitted heat, the internal absorbed heat, and the internal light flux combine to generate 3 times as much light pressure as the sunlight alone. The outward emitted heat flux light pressure works against that pressure. The sum of 3 outwards pressures and one inwards pressure is twice the outward pressure. The mass density must be doubled to compensate, for a mass per unit area of 1.5 grams per meter squared, or 1500 kilograms per kilometer squared.

If the material is carbon, with a density of 3 grams per centimeter squared, that corresponds to a thickness of 500 nanometers. Given that a graphene sheet is a fraction of a nanometer thick, that is a fairly thick structure and can contain much complexity.

The size of the shell is limited by the available material. One possible source is Neptune, with a mass of 1.02E26 kilograms. The atmosphere is approximately 1.5% methane by volume, and approximately 7% carbon by weight. If this is true of the whole planet, then Neptune contains about 7E27 grams of carbon (big if!!!).

A shell with a radius of 50 astronomical units, or 7.5E12 meters, has an area of 7E26 square meters. At 1.5 grams per square meter, that is 1E27 grams of carbon, about 15% of Neptune's carbon. Note that if Neptune has less methane, and a water or rock core, that core material can be used as "ballast" on a thinsat, with correspondingly less active carbon. One way or another, the shell of thinsats could be built with about 1% of the mass of Neptune.

Neptune has an escape velocity of 23500 meters per second, so the energy required to lift a kilogram out of its gravity well is 280 megajoules. A kilogram of hovering satellite, pre shell, in a 2.7K uniform background, covers 1300 square meters, and absorbs 2KW - if that was somehow all turned into launch energy, then the hovering satellites could lift their own mass in 140K seconds, or about 40 hours. Assuming 10% efficiency, that changes to 400 hours, the exponential growth time. Growing from a starting mass of 1E6 grams to a mass of 1E27 grams requires about 50x40 hours, about 3 months. Obviously, rates will be limited by other issues besides the power limits of partly disassembling Neptune, such as manufacturing and transit times.

A shell at 50AU will have a light flux of 0.55 watts per meter squared. The black body temperature is 56K. This will replace the current night sky temperature of the earth, which now emits 341.5 watts per meter squared, and will emit 342.05 watts per meter squared after envelopment. This will result in "global warming" of about 0.13C. Which could easily be mitigated with a few terawatts of refrigeration, or day/night albedo modification, or separating CO2 and launching some of the carbon.

The shell is outside the orbit of Pluto. At that distance, parallax is fairly small, and a tiny fraction of retro-reflectors, pointed at earth, could be used to simulate some fake stars. Since some birds navigate by the stars, this preserves their environment. It would sure upset the astronomers, but by that time, the will have moved their telescopes beyond Pluto, anyway.

Again, this is all very wild and speculative, but it does estimate the "limits to growth" for server-sky technology over the coming centuries. If we assume a 500 year buildout to 380 trillion terawatts, and start with the current 15 terawatts for human industrial consumption, then the compounded real growth rate is 6.4% per year.

Or, starting with a billion dollar investment, and pricing generation and computing at a dollar per watt, then the compounded investment growth rate will be 8.4% over 500 years. Over such large spans of time, it is very difficult to compare value, but however it is computed, this can support the growth of civilization and investment for a very long time.

And what would we do with such a shell? Perhaps some form of DigitalImmortality.

Hydrogen Ballast Shell

An even colder shell could provide more computation per watt of sunlight, because the energy per bit could be reduced. Reducing the temperature by 4x (to 14K) would require 256x the area and 16x the distance, and there is not enough carbon in the solar system to do that without some form of ballast. However, 14K is cold enough to freeze hydrogen, and that could become the ballast, perhaps frozen into lenses on the front surface of the thinsats, with the carbon concentrated at the foci. The resulting computation would be slower and more widely dispersed, but more powerful overall. Such a system could move further and further out, consuming more and more of the hydrogen in the solar system, and the shells would become increasingly hard to detect against the 2.7K cosmic background.

Perhaps that is what some "dark matter" actually is. Brownlee and Ward's "Rare Earth" teaches us that advanced civilizations are probably incredibly rare, perhaps one per several galaxies. However, in a few billion years, a few advanced civilizations may engulf most of the stars in large clusters of nearby galaxies, leading to large voids in the sky and anomalously high mass to light ratios. These large spheres would occult stars (though not galaxies) behind them; a very high resolution space telescope capable of observing individual stars billions of light years away, millions of stars, might detect a few these decade-long occultations.

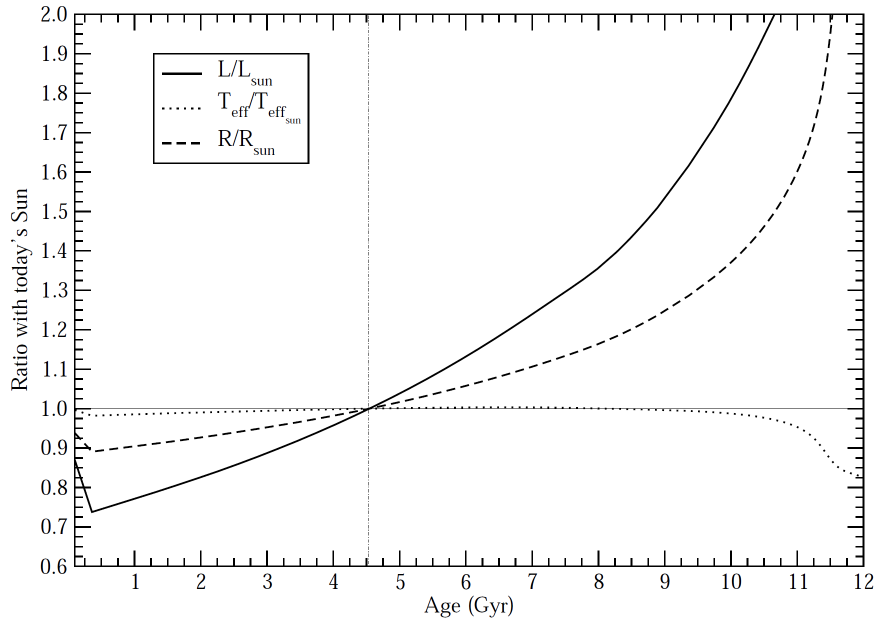

Solar heating over time

The balance of light to mass holds the thinsat shell in place. As the sun ages, irradiation increases. This can be accommodated by adding mass to the thinsats, or by making them smaller and thicker, letting some light (and heat) escape through gaps.

References

Freemann J. Dyson (1960). "Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infra-Red Radiation". Science 131 (3414): 1667–1668. doi:10.1126/science.131.3414.1667. PMID 17780673.