|

Size: 16672

Comment:

|

Size: 26210

Comment:

|

| Deletions are marked like this. | Additions are marked like this. |

| Line 4: | Line 4: |

| Summary: Light pressure adds an "eccentricity vector" of an orbit perpendicular to the light pressure. If this is added to the eccentricity vector of an equatorial, sunwards-perigee elliptical orbit with large $ J_2 $ effects, the orbit's eccentricity vector will precess to follow the apparent annual movement of the sun relative to the earth. If the solar sail ratio (the ratio of thinsat area to mass) is large, the eccentricity must be large to compensate. ------ '''Note Added 2017-05-16:''' The GEO Space Solar Power Satellite discussion below assumes equatorial orbits. Actually, SSPS will create less interference from inclined elliptical light pressure modified orbits, perhaps with apogee north of the equatorial plane for northern hemisphere customers. Peak SSPS power should occur during nighttime below, plane crossing shutdown timed for minimum need, either during the lowest demand predawn hours, or in early afternoon, when there is likely to be the most clear sky and solar power. This page should be reworked with this optimization in mind. ------ |

|

| Line 8: | Line 15: |

| For "heavy" thinsats relatively close to the earth, such as 3 gram satellites at m288, the dominant deviation from a perfect Kepler orbit is caused by the $ J_2 $ spherical harmonic of the gravity field, in turn caused by the oblateness of the spinning Earth. For small eccentricities, the eastward precession of the perigee of one elliptical equatorial orbit is proportional to the $ J_2 $ term of the WGS84 model ( -1.082626683E-03 , see Pisacane 2008 ) and the inverse of the orbit radius squared. The precession, expressed as the number complete precessions per year, is $ N_{PR} \approx -3 J_2 ( Y / P ) ( R_e / R_s ) ^ 2 ~ ~ $ where ||$ N_{PR} $ ||precessions per year caused by oblateness || ||$ J_2 $ ||spherical harmonic of gravity causing oblateness || ||$ Y $ ||year period in seconds, || ||$ P $ ||orbit period in seconds || ||$ Y/P $ ||number of orbits per year || ||$ R_e $ ||earth equatorial radius = 6378k || ||$ R_s $ ||orbit equatorial radius || || orbit || radius (RE) || orbits/year ||$N_{PR}$|| || LEO || 1.047 || 5758.5 || 17.061 || || m288 || 2.005 || 2191.5 || 1.771 || || m360 || 2.264 || 1826.2 || 1.157 || || m480 || 2.627 || 1461.0 || 0.688 || || m720 || 3.182 || 1095.7 || 0.351 || || m1440 || 4.168 || 730.5 || 0.137 || || GEO || 6.611 || 365.2 || 0.027 || == Thinsat characteristics == |

For "heavy" thinsats relatively close to the earth, such as 3 gram satellites at m288, the dominant deviation from a perfect Kepler orbit is caused by the $ J_2 $ spherical harmonic of the gravity field, in turn caused by the oblateness of the spinning Earth. For small eccentricities, the eastward precession of the perigee of one elliptical equatorial orbit is proportional to the $ J_2 $ term of the WGS84 model ( -1.082626683E-03 , see Pisacane 2008 ) and the inverse of the orbit radius squared. For small eccentricity and inclination, the precession, expressed as the number complete precessions per year, is $ N_{pr} \approx -3 J_2 ( Y / T ) ( R_e / a )^2 \approx \left( - 3 J_2 Y \mu^{1/2} / ( 2 \pi {R_E}^{3/2} ) \right) / ( {a_{RE}}^{7/2} ( 1 - e^2)^2 ) ) \approx 20.21822 / ( {a_{RE}}^{7/2} ( 1 - e^2)^2 ) ) ~ ~ ~ $ where ||$ N_{pr} $ || ||precessions per year caused by oblateness || ||$ J_2 $ || -1.082626683E-03 ||spherical harmonic of gravity causing oblateness || ||$ \mu $ || 398,600.4418 km^3^/s^2^ ||Earth gravitational constant || ||$ Y $ || 31556926 sec ||year period in seconds || ||$ T $ || ||orbit period in seconds || ||$ Y/T $ || ||number of orbits per year || ||$ e $ || || eccentricity || ||$ R_E $ || 6378.137 km ||earth equatorial radius || ||$ a $ || ||orbit semimajor axis (radius if circular) || ||$ a_{RE} $ || $ a / R_E $ ||orbit semimajor axis in earth units || Note: Pisacane's formula (5.47b) is for $ d \omega / dt ~ ~ $ in radians per second, and is in terms of $ n = 2 \pi / T ~ ~ $ . Dividing both sides by $ 2 \pi ~ $ and multiplying by $ Y ~ $ seconds per year gives the number of complete 360° (=2π radian) precessions per year. His more accurate formula has a correction for inclination, but is small for these near-equatorial near-circular orbits, so we can use the above approximation to a few percent accuracy. $ N_{pr} $ is unity - the orbit precesses accurately without light pressure - when $ a = ( (1.5 J_2 Y ( R_E )^2 / \pi )^{2/7} \mu^{1/7} $ = 15,058 km radius. || orbit ||$a_{RE}$/radius|| e || orbits/year ||$N_{pr}$|| || LEO || 1.047 || || 5758.5 || 17.061 || || m288 || 2.005 || || 2191.5 || 1.771 || apogee towards sun || || m288 || 2.005 || 0.049 || 2191.5 || 1.780 || with significant eccentricity || || m360 || 2.264 || || 1826.2 || 1.157 || more sensitive to light pressure || || m390x || 2.361 || || 1715.1 || 1.0000 || "infinite" light pressure sensitivity || || m394x || 2.374 || 0.1 || 1701.4 || 1.0000 || "infinite" light pressure sensitivity || || m407x || 2.417 || 0.2 || 1657.1 || 1.0000 || "infinite" light pressure sensitivity || || m480 || 2.627 || || 1461.0 || 0.688 || perigee towards sun || || m720 || 3.182 || || 1095.7 || 0.351 || || m1440 || 4.168 || || 730.5 || 0.137 || || GEO || 6.611 || || 365.2 || 0.027 || To keep a thinsat orbit in the same orbit and orientation to the sun, the light pressure must retard the precession at m288 and m360, and advance it at m480 and m720, so that the total precessions per year is one. More complicated orbit evolution may allow different ratios, however, eccentricity should not accumulate over many years or the apogee and perigee will eventually intersect other orbital bands, causing collisions. When $N_{pr}$ is one, the light pressure generated eccentricity accumulates, pushing the the apogee towards the west until the orbit stabilizes. Higher eccentricity increases $N_{pr}$ . This needs more study, but moving the orbit towards m390 may be a way to let light pressure drive the orbit to high eccentricity, bringing perigee down to the atmosphere and reentering the thinsats. == V2.0 thinsat characteristics == |

| Line 33: | Line 56: |

| || IR adjustment || 0.45 || || || IR reduced L.P. || 2.05e-6 || kg/m-s^2^|| |

|

| Line 35: | Line 60: |

| || thickness || 5e-5 || m || || density || 2.5e+3 || kg/m^3^ || || volume || 1.2e-6 || m^3^ || || area || 2.4e-2 || m^2^ || |

|| thickness || 44 || μm || || density || 2.7e+3 || kg/m^3^ || || area || 2.5e-2 || m^2^ || || volume || 1.1e-6 || m^3^ || |

| Line 40: | Line 65: |

| || force || 1.0944e-7 || kg-m/s^2^|| || acceleration || 3.648e-5 || m/s^2^ || |

|| force || 5.12e-8 || kg-m/s^2^|| || acceleration || 3.71e-5 || m/s^2^ || |

| Line 60: | Line 85: |

| || velocity || $ dr / dt $ || $ d\vec{ r }/dt || || unperturbed orbit velocity || $ V = \sqrt{ \mu / A } $ || || similar to Soop page 39 || || apogee || $ r_a $ || || perigee || $ r_p $ || || period || $ T = 2 \pi \sqrt{ a^3/\mu } $ || || radial velocity || $ V_r = V ( e_x sin s - e_y cos s ) $ || || similar to Soop page 39 || || tangential velocity || $ V_t = 2 V ( e_x cos s + e_y sin s ) $ || || similar to Soop page 39 || || orthogonal (North) velocity || $ V_o = V ( i_x sin s - i_y cos s ) $ || || similar to Soop page 39 || $ \vec{ I } = \left( \matrix{ sin i sin \Omega \\ -sin i cos \Omega \\ cos i } \right) $ $ \vec{ r } = \left( \matrix{ x \\ y \\ z } \right) = { { a( 1 - e^2 ) } \over { 1 + 3 cos \nu } } \left( \matrix { cos \Omega cos( \omega + \nu ) - sin \Omega sin( \omega + \nu ) cos i \\ sin \Omega cos( \omega + \nu ) - cos \Omega sin( \omega + \nu ) cos i \\ sin( \omega + \nu ) sin i } \right) $ . . . Soop pg 25 $ A \equiv $ M,,XXX,, unperturbed orbit radius . . . similar to Soop page 26 $ \vec{ i } = ( i sin( \Omega ), i cos( \Omega ) ) $ . . . Soop pg 27 $ \vec{ e } = ( e cos( \Omega + omega ), e sin( \Omega + omega ) ) $ . . . Soop pg 27 $ r \approx A + \delta a - A e cos \nu } $ . . . Soop pg 29 ---- $ s_b $ is angle at thrust . . . Soop pg 53 $ \Delta \vec{ e } = { { 2 \Delta V } over V } \left( \matrix{ cos s_b \\ sin s_b } \right) $ . . . Soup pg 54 ---- $ \sigma = { light pressure } / { mass } $ . . . after Soop pg 93 $ s $ is sidereal angle of orvir . . . Soop pg 93 text $ s_s $ is sidereal angle of Sun . . . Soop pg 93 text $ { { d\vec{ e } } \over dt } = { 2 \over V } \left( \matrix{ cos s \\ sin s } right) { { d V_t } \over dt } + { 1 \over V } \left( \matrix{ sin s \\ -cos s } right) { { d V_r } \over dt } $ . . . Soop pg 93 $ { { \partial \vec{ e } } \over { \partial t } } = { { P \sigma } \over { 2 \pi V } } \int_0^{2\pi} \left[ 2 \left( \matrix{ cos s \\ sin s } right) sin( s -s_s ) - \left( \matrix{ sin s \\ -cos s } right) cos( s - s_s) right] ds $ . . . Soop pg 93 MORE LATER == Old Light Pressure Analysis == {{{#!wiki caution '''THE FOLLOWING ANALYSIS NEEDS FIXING.''' THE ANALYSIS BELOW IS INCORRECT because there is no $ \ddot x = k x $ force. Light pressure increases apogee in the eastward orbital direction, decreases perigee in the west direction. The eclipse and J_2 and sun rotation perturbations must be made to match the light pressure perturbations, perhaps with some additional help from sideways thrust from non-perpendicular orientation. }}} I will show that for 3 gram 50 micron thick thinsats in m288 orbits, the orbital perturbations from light pressure are small, 180 meters front to back oscillations along the line of the orbit at the spring and fall equinoxes, and 165 meters front to back at the summer and winter solstices. If the satellites get thinner, the perturbations increase proportional to the area to mass ratio. If the orbits move further out, the perturbations increase proportional to the cube of the orbit radius, because the orbit period grows, and the perturbations are proportional to the square of the orbit period. There is also a cumulative perturbation caused by the eclipse time, which is probably small enough to be corrected by optical maneuvering. Previously I was not using the correct math for fictitious forces in a rotating frame. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rotating_frame has a good discussion, although they use $ \Omega $ where I use $ \omega_{m288} $. Their rotating frame does not include gravity, so the centrifugal force described here is stronger in the radial direction. Assume a circular orbit - toroidal orbits do not deviate much from that, and we can ignore Euler forces. The fictitious forces are related to the radial and tangential position from mean perturbation center, and to the tangential velocity relative to that center. An m288 orbit has the following parameters (subject to verification, please help me check them): || 3.986004418e14 m^3^/s^2^ || $ \mu_{\oplus} $ || Earth gravitational parameter || || 23.439281° || $ \phi $ || Earth axial tilt || || 12,788,866 m || $ r_{m288} $ || m288 orbit radial distance || || 80,354,815 m || || orbit circumference || || 17,280 sec || || orbit period relative to Earth surface || || 14,400 sec || || orbit period relative to Sun || || 14,393.432 sec || $ T_{m288} $ || sidereal orbit period relative to stars || || 5,582.7418 m/s || $ v_{m288} $ || orbital velocity || || 2,290.7858 sec/rad || $ 1/\omega_{m288} $ || reciprocal of angular velocity || || 4.3653142e-4 rad/sec || $ \omega_{m288} $ || angular velocity || || 2.4371020 m/s^2^ || $ a_{m288} $ || gravitational force || || 3.648e-5 m/s^2^ || $ a_{\lambda} $ || total light pressure acceleration @ 3g, 50$\mu$m glass || || 191.4 m || $ \lambda $ || related light pressure displacement, see below || || 0.161 || || Equinox eclipse fraction || || 0.111 || || Solstice eclipse fraction || In a circular orbit, the centrifugal acceleration balances the centripedal gravitational acceleration: $ v^2 / r = \omega^2 r = a = \mu_{\oplus} / r^2 ~ ~ ~ ~ = 2.4371020 m/s^2 $ at m288 $ \omega^2 = \mu_{\oplus} / r^3 $ If $ x \equiv $ the tangential distance forward of orbit center, then for small $ x $ the triangle of tangential and radial accelerations is proportional to the tangential and radial distances, from congruent triangles: $ \partial a_x / a = - \partial x / r $ $ a_x = -( a / r ) x = - \omega^2 x $ With no perturbations, the vertical acceleration is: $ a_r = \omega^2 ~ r - \mu_{\oplus} / r^2 = v^2 / r - \mu_{\oplus} / r^2 = 0 $ If the tangential velocity is perturbed, the radial acceleration is perturbed: $ \partial a_r = 2 v / r \partial v_x = 2 \omega ~ \partial v_x $ If the radial distance is perturbed, the radial acceleration is also perturbed: $ \partial a_r = ( \omega^2 + 2 \mu_{\oplus} / r^3 ) \partial r = 3 \omega^2 \partial r $ So the total radial acceleration, for small perturbations of $ y \equiv \Delta r $ and $ x $ is: $ a_y = 3 \omega^2 ~ y + 2 \omega ~ v_x $ The radial and tangential accelerations are caused by the light pressure from the Sun. This can be divided into two components, the planar light pressure parallel to the plane and the light pressure perpendicular to the plane. These are a function of the time of year $ \beta $, and the Earth's axial tilt of $ \phi = $ 23.439281° . We can compute the components from the cross product of the sunwards light pressure vector $ a_{\lambda} ~ \hat j $ and the normal vector of the equatorial plane given by $ \hat i = \sin( \phi ) \cos( \beta ) ~ $, $ ~ ~ \hat j = \sin( \phi ) \sin( \beta ) $, and $ \hat k = \cos ( \phi ) $. The perpendicular pressure is $ a_{\lambda ~ z} = a_{\lambda} \sin( \phi ) \sin( \beta ) $, and the planar pressure is $ a_{\lambda ~ p} = a_{\lambda} sqrt{ 1 - ( \sin( \phi ) \sin( \beta ) )^2 } $. At the equinoxes, $ a_{\lambda ~ z} = 0 $ and $ a_{\lambda ~ p} = a_{\lambda} $. At the solstices, $ a_{\lambda ~ z} = \pm a_{\lambda} \sin( \phi ) $ and $ a_{\lambda ~ p} = a_{\lambda} \cos( \phi ) $. The perpendicular component does not change as the object orbits. The object is displaced above or below the equatorial plane by $ z ~ = ~ a_{\lambda ~ z} / \omega^2 ~ = ~ ( a_{\lambda} / { \omega^2 } ) \sin ( \phi ) \sin( \beta ) $. Define the parameter $ \lambda ~ \equiv ~ a_{\lambda} / { \omega^2 } = $ 191.4 meters for a 3 gram, 50 $\mu$m thick glass flat sat at m288 . The z displacement varies sinusoidally between $\pm$ 76.1 meters over the course of a year, far smaller than the cross section of the toroidal orbit. $ \omega^2 = \mu_{\oplus} / r^3 $, so $ \lambda = a_{\lambda} r^3 / \mu_{\oplus} $. A thinner thinsat has higher $ a_{\lambda} $ and higher $ \lambda $. A more distant orbit also has higher $ \lambda $. For sufficiently thin satellites or large distances, the approximations above break down, and light pressure will push the satellites out of orbit, perhaps to escape velocity. The planar light pressure makes one rotation per 14400 seconds around the guiding center, and is interrupted when the satellite is eclipsed by the Earth. We will compute the effect of this later. If we approximate the rotation as the sidereal period instead, and assume we can make up for eclipse and rotation changes by maneuvering (dangerous assumption), then we can approximate the light pressure components as: $ a_{{\lambda} ~ y } = a_{\lambda ~ p} \sin( \omega t ) $ $ a_{{\lambda} ~ x } = - a_{\lambda ~ p } \cos( \omega t ) $ Assume that $ x = k \lambda \cos( \omega t ) ~ ~ $ Then $ ~ ~ ~ v_x = \dot { x } = - k \lambda \omega \sin( \omega t ) $ and $ ~ ~ ~ \ddot { x } = - k \lambda \omega^2 \cos( \omega t ) = - \omega^2 x $ The sum of the inertial force and the displacement force is equal to the light pressure: $ - a_{\lambda ~ p } \cos( \omega t ) = \ddot { x } + a_x = - \omega^2 x + - \omega^2 x = -2 \omega^2 k \lambda \cos( \omega t ) $ Dividing both sides by $ \omega^2 \cos( \omega t ) $: $ - a_{\lambda ~ p } / \omega^2 = \lambda = -2 k \lambda $. Thus, $ k = -0.5 $. Therefore $ x = - 0.5 \lambda \cos( \omega t ) $ and $ v_x = - 0.5 a_{\lambda} / \omega \sin( \omega t ) $ The acceleration of y is the $ a_y $ fictitious force plus the light pressure: $ \ddot{ y } = a_y + a_{{\lambda ~ p } ~ y } = 3 \omega^2 y + 2 \omega v_x + a_{\lambda ~ p} \sin( \omega t ) = 3 \omega^2 y + 2 \omega ( - a_{\lambda ~ p} / ( 2 \omega ) ) \sin( \omega t ) + a_{\lambda ~ p} \sin( \omega t ) = 3 \omega^2 y - a_{\lambda ~ p} \sin( \omega t ) + a_{\lambda ~ p} \sin( \omega t ) = 3 \omega^2 y $ If $ \ddot{ y } = 3 \omega^2 y $ , the only stable solution is $ y = 0 $ !!! The satellite oscillates back and forth along the path of the orbit, but is not displaced radially by light pressure. The centrifugal acceleration of the tangential velocity exactly balances the light pressure. == Perturbations because of eclipse == The above would be accurate if the earth was transparent. However, the satellite passes behind the earth for as much as 16.1% of its orbit during the equinoxes, and 11.1% at the solstices. MORE LATER |

|| velocity || $ dr / dt $ || $ d\vec{ r }/dt $ || || unperturbed orbit velocity || $ V = \sqrt{ \mu / a } $ || || similar to Soop page 39 || || apogee || $ r_a $ || || perigee || $ r_p $ || || period || $ T = 2 \pi \sqrt{ a^3/\mu } $ || || radial velocity || $ V_r = V (e_x~\sin(s)~-~e_y~\cos(s) $ || || similar to Soop page 39 || || tangential velocity || $ V_t = 2 V (e_x~\cos(s)~+~e_y~\sin(s) $ || || similar to Soop page 39 || || orthogonal (North) velocity || $ V_o = V (i_x~\sin(s)~-~i_y~\cos(s) $ || || similar to Soop page 39 || $ \vec{ I } = \left( \matrix{ \sin(i)~\sin(\Omega) \\ \sin(i)~\cos(\Omega) \\ \cos(i) } \right) $ $ \vec{ r } = \left( \matrix{ x \\ y \\ z } \right) = { \Large { { a( 1 - e^2 ) } \over { 1 + 3 \cos(\nu) } } } \left( \matrix { \cos(\Omega)~\cos( \omega+\nu ) - \sin(\Omega)\sin(\omega+\nu )~\cos(i) \\ \sin( \Omega ) ~\cos( \omega+\nu ) - \cos(\Omega) \sin( \omega+\nu )~\cos(i) \\ \sin( \omega+\nu )~\sin(i) } \right) ~~~$ . . . Soop pg 25 $ a \equiv ~~~$ M,,XXX,, unperturbed orbit radius . . . similar to Soop page 26 $ \vec{ i } = ( i~\sin( \Omega ), i~\cos( \Omega ) ) ~~~$ . . . Soop pg 27 $ \vec{ e } = ( e~\cos( \Omega + \omega ), e~\sin( \Omega +\omega ) ) ~~~$ . . . Soop pg 27 $ r \approx A + \delta a~-~A e \cos(\nu) ~~~$ . . . Soop pg 29 ---- $ s_b ~~~$ is angle at thrust . . . Soop pg 53 $ { \large { \Delta \vec{ e } } = { \Large { { 2 \Delta V } \over V } }} \left( \matrix{ \cos(s_b) \\ \sin(s_b) } \right) ~~~$ . . . Soup pg 54 ---- $ \lambda ~~~$ = 3.65e-5 m/s^2^ is the light pressure acceleration, which is the solar pressure $ P $ ( 4.56e-6 N/m^2^ ) times the area to mass ratio $ \sigma $, 8.333 m^2^/kg = ( 0.025 m^2^ / 0.003 kg ) for a 44 μm thinsat. . . similar to Soop pg 93 $ s ~~~$ is sidereal angle of orbit . . . Soop pg 93 text $ s_s ~~~$ is sidereal angle of Sun . . . Soop pg 93 text $ { \Large { { d\vec{ e_{\lambda} } } \over dt } = { 2 \over V } } \left( \matrix{ \cos(s) \\ \sin(s) } \right) { \Large { { d V_t } \over dt } + { 1 \over V } } \left( \matrix{ \sin(s) \\ -\cos(s) } \right) { \Large { { d V_r } \over dt } } ~ ~ ~ $ . . . Soop pg 93 $ { \Large { { \partial \vec{ e_{\lambda} } } \over { \partial t } } = { \lambda \over { 2 \pi V } } \int_0^{2\pi} } \left[ 2 \left( \matrix{ \cos(s) \\ \sin(s) } \right) \sin(s-s_s) - \left( \matrix{ ~\sin(s) \\ -\cos(s) } \right) \cos(s-s_s) \right] ds ~ ~ ~ $ . . . Soop pg 93 $ { \Large { { \partial \vec{ e_{\lambda} } } \over { \partial t } } = { \lambda \over { 2 \pi V } }\int_0^{2\pi} } \left[ 1.5 \left( \matrix{ -\sin(s_s) \\ ~\cos(s_s) } \right) + 0.5 \left( \matrix{ ~ ~ \sin(2*s-s_s) \\ -\cos(2*s-s_s) } \right) \right] ds ~ ~ ~ $ . . . This is the equation if $ \lambda $ is constant $ { \Large { { \partial \vec{ e_{\lambda} } } \over { \partial t } } = { \lambda \over { 2 \pi V } } } \left[ 1.5 \times 2 \pi \left( \matrix{ -\sin(s_s) \\ ~\cos(s_s) } \right) + 0.5 { \Large { \int_0^{2\pi} } } \left( \matrix{ ~ ~ \sin(2s-s_s) \\ -\cos(2s-s_s) } \right) ds \right] $ $ { \Large { { \partial \vec{ e_{\lambda} } } \over { \partial t } } = { { 3 \lambda } \over { 2 V } } } \left( \matrix{ -\sin(s_s) \\ ~\cos(s_s) } \right) + { \Large { \lambda \over { 4 \pi V } } { \int_0^{2\pi} } } \left( \matrix{ ~ ~ \sin(2s-s_s) \\ -\cos(2s-s_s) } \right) ds ~ ~ ~ $ . . . the integral is zero for constant illumination $ { \Large { { \partial \vec{ e_{\lambda} } } \over { \partial t } } = { { 3 \lambda } \over { 2 V } } } \left( \matrix{ - \sin(s_s) \\ ~ \cos(s_s) } \right) ~ ~ ~ $ perpendicular to the Sun, perturbing the eccentricity vector eastward . . . Soop page 95 $ Y ~~~$ = one year . . . Soop page 95 $ { { \vec{ e_{\lambda} } ( t ) = } { \Large { { 3 \lambda Y } \over { 4 \pi V } } } } \left( \matrix{ \cos(s_s) \\ \sin(s_s) } \right) ~~~$ . . . Soop page 95 For a prograde orbit, this vector points eastward along the orbit, and has a magnitude of $ e_{\lambda} = { \Large { { 3 \lambda Y } \over { 4 \pi V } } } = { \Large { { 3 P \sigma Y } \over { 4 \pi V } } } $ Without the J2 modifications, a light-pressure-modified orbit (with $ \vec e $ and perigee pointing towards the sun) for a 3 gram, 240cm^2^ thinsat ( σ = 8 m^2^kg^-1^ ) would have a light pressure eccentricity of: $ e_{\lambda} = { \Large { { 3 \lambda Y } \over { 4 \pi V } } = { { 3 \times ~ {3.65e-5} ~ \times ~ 3.156e7 } \over { 4 \pi ~\times ~5582.74 } } } ~ ~ ~ $ = 0.049 The eccentricity of the light modified orbit is around 0.05 . If the thinsat is thinner, that gets larger. It also gets larger for more distant orbits ( M360, M480, etc.). Proportional to period T^1/3^ MoreLater ---- === Inclination to the Ecliptic === Because of the inclination of the orbit relative to the ecliptic, some of the light pressure is towards the south during summer and the north during winter. The eccentricity-modifying light pressure is a function of the sun's declination $ \delta_\odot $ : $ \lambda = \lambda_0 ~ \cos(\delta_\odot) ~ ~ ~$ where: $ \delta_\odot = \arcsin \left [ \sin \left ( -23.44^\circ \right ) \cdot \cos \left ({{360^{\circ}\times(day+10)}\over{365}} \right ) \right ] ~~~$ where $ day $ is the day of the year starting with Jan 1 = 0 thus $ \lambda = \lambda_0 \sqrt{ 1 - \left [ \sin \left ( -23.44^\circ \right ) \cdot \cos \left ({{360^{\circ}\times(day+10)}\over{365}} \right ) \right ]^2 } ~ ~ ~$ averaging over an orbit $ \bar { \lambda } \approx 0.9592 ~ \lambda_0 ~~~$ so $ e_{\lambda} ~~~$ is reduced somewhat, to 0.047 . NOTE ADDED: This needs refinement. When the orbit is inclined, less is in eclipse, so the thrust increases due to that. MoreLater ---- === Modifications for earth shadow eclipse time and night pollution minimization === The eclipse time has a small effect, because we are only subtracting an acceleration approximately equal to sin^2^ of the +/- 30° angle behind the earth. Integrating from -150° to 150° subtracts approximately 1/24 of the effect, so $ e_{\lambda} $ is reduced to about 0.045 . A larger effect on light pressure is the intentional tilting of thinsats to minimize night time light pollution. Thinsats will be turned towards the terminator as they pass into the back half of the orbit. For M288 and lower, the orbits will have an apogee in the back, and orbit slower and spend longer in this reduced light (and light pressure) condition. Soop's integral is intended for nearly circular GEO orbits, and assumes both $ ds / dt $ and $ \sigma $ (and thus $ \lambda $) are approximately constant. With the night light pollution minimization manuever, multiply $ \lambda $ by F( s - s_s )$. Integrate: $ { \Large { { \partial \vec{ e_{\lambda} } } \over { \partial t } } = { 1 \over { 2 \pi V } } \int_0^{2\pi} } \lambda F( s - s_s ) \left[ 1.5 \left( \matrix{ -\sin(s_s) \\ ~\cos(s_s) } \right) + 0.5 \left( \matrix{ ~ ~ \sin(2*s-s_s) \\ -\cos(2*s-s_s) } \right) \right] ds ~ ~ ~ $ We can simplify and use sun angle zero, and integrate over the orbit: $ { \Large { { \partial \vec{ e_{\lambda} } } \over { \partial t } } = { \lambda \over { 2 \pi V } } \int_0^{2\pi} } F( s ) \left[ 1.5 \left( \matrix{ 0 \\ 1 } \right) + 0.5 \left( \matrix{ ~ ~ \sin(2*s) \\ -\cos(2*s) } \right) \right] ds ~ ~ ~ $ ||<-2> $ s $ || $ F( s ) $ || || from || to || for m288 orbit || || $ ~ -\pi/2 $ || $ ~ ~ \pi/2 $ ||$ 1 $ (maximum) || || $ ~ ~ \pi/2 $ || $ ~ 5\pi/6 $ ||$ \Large{{~2\sin(s)-1}\over \sqrt{5-4\sin(s)}} $|| || $ ~ 5\pi/6 $ || $ -5\pi/6 $ || 0 (eclipse) || || $ -5\pi/6 $ || $ ~ -\pi/2 $ ||$ \Large{{-2\sin(s)-1}\over \sqrt{5+4\sin(s)}} $|| If we integrate function $F( s )$ times the sin() and cos() terms (with this program:[[attachment:sunint.c|sunint.c]]), we get a vector of $\left( \matrix{ 0 \\ 0.732 } \right) $, slightly higher magnitude than the power multiplier, 0.689 . If we also assume a multiplier of 0.45 due to [[ IRfilter | front side infrared filtering]] (0.333 ideal), the sun thrust power is multiplied by $ M $ = 0.33. Assuming a sail ratio $ \sigma $ = 8.333 m^2^/kg (A 3 gram, 250cm^2^ thinsat), $ e_{\lambda} = { \Large { { 3 M P \sigma Y } \over { 4 \pi V } } = { { 3 ~ \times ~ 0.33 ~ \times ~ {4.56e-6} ~ \times ~ 8.333 ~ \times ~ 3.156e7 } \over { 4 \pi ~\times ~5582.74 } } } ~ ~ ~ $ = 0.0169 ---- === Combining with the J2 Modification === The simplest case for M288 is an eccentricity vector diagram like so: {{ attachment:LightOrbit288.png | | width=640 }} For a bounded elliptical M288 orbit, $ e_{J2} = 1.771 \times e $ and $ e_{ year } = e $, so with apogee towards the sun, $ e_{ \lambda } = 0.771 \times e $. That means that for a 44μm 8.333 m^2^/kg thinsat, $ e $ = 0.0169 / 0.771 or 0.022, or perhaps a little larger because of the twice-annual variation in tangential light acceleration. Assume that the distance to orbits near M288 (for example, LAGEOS at 12331 km apogee) should be at least 0.022*12789 km = 280km, so there should be no valuable equatorial crossers between 12509 and 13069 km . M360 orbits (The O3b satellites) have a J2 excess of 0.157 instead of 0.771, which means that the eccentricity to mass ratio will be almost 5 times larger than M288. M360 does not look like a practical orbit for low mass thinsats. Cheap launch and ballast will change this. {{ attachment:LightOrbit480.png | | width=640 }} The M480 orbit ( 16756km ) is slower so $ e_{\lambda} $ is larger: $ e_{\lambda488} = { \Large { { 3 M P \sigma Y } \over { 4 \pi V } } = { { 3 ~ \times ~ 0.33 ~ \times ~ 4.56E-6 ~ \times ~ 8.333 ~ \times ~ 3.156e7 } \over { 4 \pi ~ \times ~ 4877.51 } } } ~ ~ ~ $ = 0.0196 . For a bounded elliptical M480 orbit, $ e_{J2} = 0.688 \times e $ and $ e_{ year } = e ~ ~ ~ $ , so with perigee towards the sun, $ e_{ \lambda } = 0.312 \times e ~ ~ ~ $. That means that for a 44μm 8.333 m^2^/kg thinsat, $ e ~ $ = 0.0198 / 0.312 or 0.0633 . Assume that the distance to orbits near M480 should be at least 0.0633*16756 km = 871 km, so there should be no valuable equatorial crossers between 15885 and 17627 km . <<Anchor(Eccentric)>> ~-'' http://server-sky.com/LightOrbit#Eccentric ''-~ {{ attachment:K0_lighteccentric.png | | width=800 }} <<Anchor(AlDens)>> ~-'' http://server-sky.com/LightOrbit#AlDens ''-~ '''Note added 2021 September 26:''' Thickesses are equivalent mass of aluminum; 100 micrometers of 2700 kg/m³ aluminum is 270 grams/m² or 27 mg/cm². This might be implemented as a ''very'' thin foil with tiny lensed solar cells and thicker-lensed computation chips. The lens globs can focus sunlight while dispersing some of the high energy radiation. Electronics should be redundant and error-correcting. Note that a VAST amount of computation and memory can be crammed into a submillimeter silicon die using a deep-submicron process and radiation-insensitive "leaky" gate oxides. Note also an asymptote in the graph, between M360 and M480. Orbits are destabilized by light pressure in this zone. It is interesting and perhaps scientifically important that this radius is near the radius of the gap between the inner ( electron/proton plasma) and outer (electron) van Allen belts. ---- === Inclination - Flattened Toroidal Orbit === Because of the eccentricity, we will incline the orbit, so that the central orbit can be set aside for heavier objects. We should consider a flattened torus so that this orbit does not go too far south or north. If we make the inclination for the M288 orbit ( $ e ~~~$ = 0.0 ) 0.5°, then the orbit passes above and below the 12789 km central orbit by 112 km, compared to the 280 km sideways distance. The circular orbital speed at M288 is $ V $ = 5583 m/s. The relative velocity of the two orbits at crossing ( r = A, $ \cos( \theta ) = - e ~ ~ $ = 0.022, or $ \theta ~ ~ $ = 91.26° ) is: || tangential || $ e V \cos( \theta ) = e^2 V $ || 2.7 m/s || || radial || $ e V \sin( \theta ) $ || 122.5 m/s || || total || $ e V $ || 122.5 m/s || The "velocity shear" across the orbit is ( 122.5 m/s / 112km ) 1.09 m/s per km or 1.09e-3 / second. If we imagine a series of increasing-weight thinsats around the central orbit, lighter at the edges and denser near the central orbit, then M288 orbits that differ in velocity by 1 m/s will always more than 910 meters apart. The locus of all these orbits will be a "double Möbius" strip (one full turn), with one edge along the circular central orbit and the other edge wrapping around it toroidally. MoreLater ---- === A note about thinsats and Space Based Solar Power in GEO === The J,,2,, oblateness effect is almost nonexistent in GEO. The discussion by Soop above is focused on GEO satellites, which must be well positioned with very small errors in North/South and East/West position. The North/South position is strongly perturbed by tidal effects from the Sun and Moon, while the East/West position is perturbed by higher order nonuniformities in the longitudinal gravity field. These nonuniformities want to drag satellites towards 75°E and 105°W, while light pressure effects want to drive the orbit elliptical as above. GEO is prime real estate; almost every orbital slot has an expensive satellite in it, and satellites are typically constrained to stay in an east/west '''dead band''' of about 0.1° so they do not encroach on their neighbors. Further, GEO comsats usually talk to fixed high gain dishes on the ground, with narrow beam angles, so they are constrained to 0.1° of drift in all directions. Server sky ground antennas are assumed to be steerable, so they are free to drift somewhat to the north and south. But they must be constrained east/west . The total station keeping thruster budget for a GEO satellite averages 50 m/s per year or 1.6 μm/s^2^. With a conventional satellite dry weight of 1.5 tonnes, the station keeping requires an average of 2.4 mN. Traditional satellites use solar panels massing about 500kg/10kW (WAG), and assuming 20% efficiency ( 270w/m^2^ WAG) these 40m^2^ satellites are subject to 180 μN of sunlight force, or 0.12 μm/s^2^ of acceleration, smaller than the station keeping force. Solar power satellites are intended to produce 1 kW per kilogram, which increases the forces needed for sunlight station keeping to perhaps 2.0 μm/s^2^, or 110 m/s/year . If we do not correct the sunlight forces, then $ e_{\lambda-GEO} = { { 3 \lambda Y } \over { 4 \pi V } } = { { 3 \times 2e-6 \times 3.156e7 } \over { 4\times\pi\times 3074.6 } } $ = 5e-3 . The daily east/west drift would be about ±0.01 radians or 0.57° - clearly unacceptable in the tightly constrained GEO orbit. The mass must be increased to 6kg/kW, and thinsats would require similar mass to area ratios. Although SSPS in GEO is "always on", it may be as much as 6 times heavier and 13.3 times harder to launch than thinsats to M480 - even with thinsats at 30% utilization to one ground rectenna, the launch cost per Watt is 4x cheaper. M480 thinsats are also 2.5x closer, and antenna sizes can be 6x smaller. If the rectennas are 6x cheaper, then we can deploy 6 for the cost of 1 GEO rectenna, and sell all the power from the thinsats, all around the world, bringing utilization closer to 100%. Note that in the real world of grid power, demand is not constant over a day, and peaking sources are expensive. If SBSP can supply peak load, by switching the beam to rectennas in other time zones, the power becomes much more valuable. Overall, SBSP supplied with MEO thinsats can be up to 20x more profitable than power supplied from GEO satellites. In addition, because the arrays can be in inclined orbits, we the rectenna elevation angles can be reduced, and the power beams are less likely to interfere with signal beams from GEO communication satellites. === Lagrange Orbits and Light Pressure === Because of the biological effects of nocturnal illumination, both MEO and GEO SBSP deployment will be limited anyway. It is better to deploy large scale SBSP at the Lunar Lagrange points, where lunar perturbations and solar perturbations can be balanced with much lighter thinsats in very large arrays, perhaps with significant north/south inclination to the lunar orbital plane. MoreLater |

Light Pressure Modified Orbits

Summary: Light pressure adds an "eccentricity vector" of an orbit perpendicular to the light pressure. If this is added to the eccentricity vector of an equatorial, sunwards-perigee elliptical orbit with large J_2 effects, the orbit's eccentricity vector will precess to follow the apparent annual movement of the sun relative to the earth. If the solar sail ratio (the ratio of thinsat area to mass) is large, the eccentricity must be large to compensate.

Note Added 2017-05-16: The GEO Space Solar Power Satellite discussion below assumes equatorial orbits. Actually, SSPS will create less interference from inclined elliptical light pressure modified orbits, perhaps with apogee north of the equatorial plane for northern hemisphere customers. Peak SSPS power should occur during nighttime below, plane crossing shutdown timed for minimum need, either during the lowest demand predawn hours, or in early afternoon, when there is likely to be the most clear sky and solar power. This page should be reworked with this optimization in mind.

Light pressure effects modify thinsat array orbits. In the nominal orbit, thinsats are at "half thrust", with each thruster half mirror and half transparent. Variations to full or zero reflectivity, and full or zero thrust, allow each thinsat to maneuver in relation to the array, or for the array as a whole to maneuver around its assigned centerpoint. The following is an analysis of two effects, earth oblateness and nominal half-thrust light pressure, on the orbit. We will assume that the arrays maintain a constant, slightly elliptical orbit that precesses once per year in the equatorial plane. We will assume continuous illumination tangential to the equatorial plane, and zero light pressure effects from Earth albedo or black-body radiation, and no solar or lunar tides. These assumptions are somewhat crude approximations to get us into the ballpark of a solution. Precise solutions will probably demand accurate numerical solutions simulating many years of orbital evolution.

Earth Oblateness

For "heavy" thinsats relatively close to the earth, such as 3 gram satellites at m288, the dominant deviation from a perfect Kepler orbit is caused by the J_2 spherical harmonic of the gravity field, in turn caused by the oblateness of the spinning Earth. For small eccentricities, the eastward precession of the perigee of one elliptical equatorial orbit is proportional to the J_2 term of the WGS84 model ( -1.082626683E-03 , see Pisacane 2008 ) and the inverse of the orbit radius squared. For small eccentricity and inclination, the precession, expressed as the number complete precessions per year, is N_{pr} \approx -3 J_2 ( Y / T ) ( R_e / a )^2 \approx \left( - 3 J_2 Y \mu^{1/2} / ( 2 \pi {R_E}^{3/2} ) \right) / ( {a_{RE}}^{7/2} ( 1 - e^2)^2 ) ) \approx 20.21822 / ( {a_{RE}}^{7/2} ( 1 - e^2)^2 ) ) ~ ~ ~ where

N_{pr} |

|

precessions per year caused by oblateness |

J_2 |

-1.082626683E-03 |

spherical harmonic of gravity causing oblateness |

\mu |

398,600.4418 km3/s2 |

Earth gravitational constant |

Y |

31556926 sec |

year period in seconds |

T |

|

orbit period in seconds |

Y/T |

|

number of orbits per year |

e |

|

eccentricity |

R_E |

6378.137 km |

earth equatorial radius |

a |

|

orbit semimajor axis (radius if circular) |

a_{RE} |

a / R_E |

orbit semimajor axis in earth units |

Note: Pisacane's formula (5.47b) is for d \omega / dt ~ ~ in radians per second, and is in terms of n = 2 \pi / T ~ ~ . Dividing both sides by 2 \pi ~ and multiplying by Y ~ seconds per year gives the number of complete 360° (=2π radian) precessions per year. His more accurate formula has a correction for inclination, but is small for these near-equatorial near-circular orbits, so we can use the above approximation to a few percent accuracy.

N_{pr} is unity - the orbit precesses accurately without light pressure - when a = ( (1.5 J_2 Y ( R_E )^2 / \pi )^{2/7} \mu^{1/7}

- = 15,058 km radius.

orbit |

a_{RE}/radius |

e |

orbits/year |

N_{pr} |

|

LEO |

1.047 |

|

5758.5 |

17.061 |

|

m288 |

2.005 |

|

2191.5 |

1.771 |

apogee towards sun |

m288 |

2.005 |

0.049 |

2191.5 |

1.780 |

with significant eccentricity |

m360 |

2.264 |

|

1826.2 |

1.157 |

more sensitive to light pressure |

m390x |

2.361 |

|

1715.1 |

1.0000 |

"infinite" light pressure sensitivity |

m394x |

2.374 |

0.1 |

1701.4 |

1.0000 |

"infinite" light pressure sensitivity |

m407x |

2.417 |

0.2 |

1657.1 |

1.0000 |

"infinite" light pressure sensitivity |

m480 |

2.627 |

|

1461.0 |

0.688 |

perigee towards sun |

m720 |

3.182 |

|

1095.7 |

0.351 |

|

m1440 |

4.168 |

|

730.5 |

0.137 |

|

GEO |

6.611 |

|

365.2 |

0.027 |

To keep a thinsat orbit in the same orbit and orientation to the sun, the light pressure must retard the precession at m288 and m360, and advance it at m480 and m720, so that the total precessions per year is one. More complicated orbit evolution may allow different ratios, however, eccentricity should not accumulate over many years or the apogee and perigee will eventually intersect other orbital bands, causing collisions.

When N_{pr} is one, the light pressure generated eccentricity accumulates, pushing the the apogee towards the west until the orbit stabilizes. Higher eccentricity increases N_{pr} . This needs more study, but moving the orbit towards m390 may be a way to let light pressure drive the orbit to high eccentricity, bringing perigee down to the atmosphere and reentering the thinsats.

V2.0 thinsat characteristics

Light pressure parameters |

|||

Light Power |

1367 |

W/m2 |

|

Speed of Light |

2.998e+8 |

m/s |

|

Light pressure |

4.56e-6 |

kg/m-s2 |

|

IR adjustment |

0.45 |

|

|

IR reduced L.P. |

2.05e-6 |

kg/m-s2 |

|

Thinsat parameters |

|||

mass |

3e-3 |

kg |

|

thickness |

44 |

μm |

|

density |

2.7e+3 |

kg/m3 |

|

area |

2.5e-2 |

m2 |

|

volume |

1.1e-6 |

m3 |

|

length |

18.5e-2 |

m |

rounded thruster top |

force |

5.12e-8 |

kg-m/s2 |

|

acceleration |

3.71e-5 |

m/s2 |

|

Light Pressure

A useful starting analysis is in E. M. Soop, "Handbook of Geostationary Orbits". Soop's analysis is for geostationary orbits, which are rarely in eclipse and much less subject to J2. perturbations. However, Soop's analysis is a good starting point. The book is practical, focused on satellite operation, the math is moderate, and the references are rather skimpy.

Soop analyzes the geostationary orbit in the cartesian MEGSD (Mean Equatorial Geocentric System of Date) coordinate system (pg. 15). This system is approximate and quasi-inertial; very accurate analyses will require full numerical solutions. The X-Y plane of MEGSD is the Earth's equatorial plane (which slowly precesses 0.014° per year), with the x direction oriented sidereally, towards the Vernal Equinox or First Point of Aries, where the equatorial plane and the ecliptic plane intersect. The Z direction is north.

Soop describes the various orbital parameters as both scalars (pg 21) and vectors. Unlike Soop, I will use \vec{ x } instead of \overline{ x } .

|

scalar |

vector |

|

semimajor axis |

a |

||

eccentricity |

e |

\vec{ e } |

|

inclination |

i |

\vec{ I } |

|

right ascension of the ascending node |

\Omega |

||

argument of perigee |

\omega |

||

true anomaly |

\nu |

||

unperturbed orbit angle |

s |

||

radius |

r |

\vec{ r } |

|

velocity |

dr / dt |

d\vec{ r }/dt |

|

unperturbed orbit velocity |

V = \sqrt{ \mu / a } |

|

similar to Soop page 39 |

apogee |

r_a |

||

perigee |

r_p |

||

period |

T = 2 \pi \sqrt{ a^3/\mu } |

||

radial velocity |

V_r = V (e_x~\sin(s)~-~e_y~\cos(s) |

|

similar to Soop page 39 |

tangential velocity |

V_t = 2 V (e_x~\cos(s)~+~e_y~\sin(s) |

|

similar to Soop page 39 |

orthogonal (North) velocity |

V_o = V (i_x~\sin(s)~-~i_y~\cos(s) |

|

similar to Soop page 39 |

\vec{ I } = \left( \matrix{ \sin(i)~\sin(\Omega) \\ \sin(i)~\cos(\Omega) \\ \cos(i) } \right)

\vec{ r } = \left( \matrix{ x \\ y \\ z } \right) = { \Large { { a( 1 - e^2 ) } \over { 1 + 3 \cos(\nu) } } } \left( \matrix { \cos(\Omega)~\cos( \omega+\nu ) - \sin(\Omega)\sin(\omega+\nu )~\cos(i) \\ \sin( \Omega ) ~\cos( \omega+\nu ) - \cos(\Omega) \sin( \omega+\nu )~\cos(i) \\ \sin( \omega+\nu )~\sin(i) } \right) ~~~ . . . Soop pg 25

a \equiv ~~~ MXXX unperturbed orbit radius . . . similar to Soop page 26

\vec{ i } = ( i~\sin( \Omega ), i~\cos( \Omega ) ) ~~~ . . . Soop pg 27

\vec{ e } = ( e~\cos( \Omega + \omega ), e~\sin( \Omega +\omega ) ) ~~~ . . . Soop pg 27

r \approx A + \delta a~-~A e \cos(\nu) ~~~ . . . Soop pg 29

s_b ~~~ is angle at thrust . . . Soop pg 53

{ \large { \Delta \vec{ e } } = { \Large { { 2 \Delta V } \over V } }} \left( \matrix{ \cos(s_b) \\ \sin(s_b) } \right) ~~~ . . . Soup pg 54

\lambda ~~~ = 3.65e-5 m/s2 is the light pressure acceleration, which is the solar pressure P ( 4.56e-6 N/m2 ) times the area to mass ratio \sigma , 8.333 m2/kg = ( 0.025 m2 / 0.003 kg ) for a 44 μm thinsat. . . similar to Soop pg 93

s ~~~ is sidereal angle of orbit . . . Soop pg 93 text

s_s ~~~ is sidereal angle of Sun . . . Soop pg 93 text

{ \Large { { d\vec{ e_{\lambda} } } \over dt } = { 2 \over V } } \left( \matrix{ \cos(s) \\ \sin(s) } \right) { \Large { { d V_t } \over dt } + { 1 \over V } } \left( \matrix{ \sin(s) \\ -\cos(s) } \right) { \Large { { d V_r } \over dt } } ~ ~ ~ . . . Soop pg 93

{ \Large { { \partial \vec{ e_{\lambda} } } \over { \partial t } } = { \lambda \over { 2 \pi V } } \int_0^{2\pi} } \left[ 2 \left( \matrix{ \cos(s) \\ \sin(s) } \right) \sin(s-s_s) - \left( \matrix{ ~\sin(s) \\ -\cos(s) } \right) \cos(s-s_s) \right] ds ~ ~ ~ . . . Soop pg 93

{ \Large { { \partial \vec{ e_{\lambda} } } \over { \partial t } } = { \lambda \over { 2 \pi V } }\int_0^{2\pi} } \left[ 1.5 \left( \matrix{ -\sin(s_s) \\ ~\cos(s_s) } \right) + 0.5 \left( \matrix{ ~ ~ \sin(2*s-s_s) \\ -\cos(2*s-s_s) } \right) \right] ds ~ ~ ~ . . . This is the equation if \lambda is constant

{ \Large { { \partial \vec{ e_{\lambda} } } \over { \partial t } } = { \lambda \over { 2 \pi V } } } \left[ 1.5 \times 2 \pi \left( \matrix{ -\sin(s_s) \\ ~\cos(s_s) } \right) + 0.5 { \Large { \int_0^{2\pi} } } \left( \matrix{ ~ ~ \sin(2s-s_s) \\ -\cos(2s-s_s) } \right) ds \right]

{ \Large { { \partial \vec{ e_{\lambda} } } \over { \partial t } } = { { 3 \lambda } \over { 2 V } } } \left( \matrix{ -\sin(s_s) \\ ~\cos(s_s) } \right) + { \Large { \lambda \over { 4 \pi V } } { \int_0^{2\pi} } } \left( \matrix{ ~ ~ \sin(2s-s_s) \\ -\cos(2s-s_s) } \right) ds ~ ~ ~ . . . the integral is zero for constant illumination

{ \Large { { \partial \vec{ e_{\lambda} } } \over { \partial t } } = { { 3 \lambda } \over { 2 V } } } \left( \matrix{ - \sin(s_s) \\ ~ \cos(s_s) } \right) ~ ~ ~ perpendicular to the Sun, perturbing the eccentricity vector eastward . . . Soop page 95

Y ~~~ = one year . . . Soop page 95

{ { \vec{ e_{\lambda} } ( t ) = } { \Large { { 3 \lambda Y } \over { 4 \pi V } } } } \left( \matrix{ \cos(s_s) \\ \sin(s_s) } \right) ~~~ . . . Soop page 95

For a prograde orbit, this vector points eastward along the orbit, and has a magnitude of

e_{\lambda} = { \Large { { 3 \lambda Y } \over { 4 \pi V } } } = { \Large { { 3 P \sigma Y } \over { 4 \pi V } } }

Without the J2 modifications, a light-pressure-modified orbit (with \vec e and perigee pointing towards the sun) for a 3 gram, 240cm2 thinsat ( σ = 8 m2kg-1 ) would have a light pressure eccentricity of:

e_{\lambda} = { \Large { { 3 \lambda Y } \over { 4 \pi V } } = { { 3 \times ~ {3.65e-5} ~ \times ~ 3.156e7 } \over { 4 \pi ~\times ~5582.74 } } } ~ ~ ~ = 0.049

The eccentricity of the light modified orbit is around 0.05 . If the thinsat is thinner, that gets larger. It also gets larger for more distant orbits ( M360, M480, etc.). Proportional to period T1/3

Inclination to the Ecliptic

Because of the inclination of the orbit relative to the ecliptic, some of the light pressure is towards the south during summer and the north during winter. The eccentricity-modifying light pressure is a function of the sun's declination \delta_\odot :

\lambda = \lambda_0 ~ \cos(\delta_\odot) ~ ~ ~

where:

\delta_\odot = \arcsin \left [ \sin \left ( -23.44^\circ \right ) \cdot \cos \left ({{360^{\circ}\times(day+10)}\over{365}} \right ) \right ] ~~~ where day is the day of the year starting with Jan 1 = 0

thus

\lambda = \lambda_0 \sqrt{ 1 - \left [ \sin \left ( -23.44^\circ \right ) \cdot \cos \left ({{360^{\circ}\times(day+10)}\over{365}} \right ) \right ]^2 } ~ ~ ~

averaging over an orbit

\bar { \lambda } \approx 0.9592 ~ \lambda_0 ~~~ so e_{\lambda} ~~~ is reduced somewhat, to 0.047 .

NOTE ADDED: This needs refinement. When the orbit is inclined, less is in eclipse, so the thrust increases due to that.

Modifications for earth shadow eclipse time and night pollution minimization

The eclipse time has a small effect, because we are only subtracting an acceleration approximately equal to sin2 of the +/- 30° angle behind the earth. Integrating from -150° to 150° subtracts approximately 1/24 of the effect, so e_{\lambda} is reduced to about 0.045 .

A larger effect on light pressure is the intentional tilting of thinsats to minimize night time light pollution. Thinsats will be turned towards the terminator as they pass into the back half of the orbit. For M288 and lower, the orbits will have an apogee in the back, and orbit slower and spend longer in this reduced light (and light pressure) condition.

Soop's integral is intended for nearly circular GEO orbits, and assumes both ds / dt and \sigma (and thus \lambda ) are approximately constant. With the night light pollution minimization manuever, multiply \lambda by F( s - s_s )$.

Integrate:

{ \Large { { \partial \vec{ e_{\lambda} } } \over { \partial t } } = { 1 \over { 2 \pi V } } \int_0^{2\pi} } \lambda F( s - s_s ) \left[ 1.5 \left( \matrix{ -\sin(s_s) \\ ~\cos(s_s) } \right) + 0.5 \left( \matrix{ ~ ~ \sin(2*s-s_s) \\ -\cos(2*s-s_s) } \right) \right] ds ~ ~ ~

We can simplify and use sun angle zero, and integrate over the orbit:

{ \Large { { \partial \vec{ e_{\lambda} } } \over { \partial t } } = { \lambda \over { 2 \pi V } } \int_0^{2\pi} } F( s ) \left[ 1.5 \left( \matrix{ 0 \\ 1 } \right) + 0.5 \left( \matrix{ ~ ~ \sin(2*s) \\ -\cos(2*s) } \right) \right] ds ~ ~ ~

s |

F( s ) |

|

from |

to |

for m288 orbit |

~ -\pi/2 |

~ ~ \pi/2 |

1 (maximum) |

~ ~ \pi/2 |

~ 5\pi/6 |

\Large{{~2\sin(s)-1}\over \sqrt{5-4\sin(s)}} |

~ 5\pi/6 |

-5\pi/6 |

0 (eclipse) |

-5\pi/6 |

~ -\pi/2 |

\Large{{-2\sin(s)-1}\over \sqrt{5+4\sin(s)}} |

If we integrate function F( s ) times the sin() and cos() terms (with this program:sunint.c), we get a vector of \left( \matrix{ 0 \\ 0.732 } \right) , slightly higher magnitude than the power multiplier, 0.689 .

If we also assume a multiplier of 0.45 due to front side infrared filtering (0.333 ideal), the sun thrust power is multiplied by M = 0.33. Assuming a sail ratio \sigma = 8.333 m2/kg (A 3 gram, 250cm2 thinsat),

e_{\lambda} = { \Large { { 3 M P \sigma Y } \over { 4 \pi V } } = { { 3 ~ \times ~ 0.33 ~ \times ~ {4.56e-6} ~ \times ~ 8.333 ~ \times ~ 3.156e7 } \over { 4 \pi ~\times ~5582.74 } } } ~ ~ ~ = 0.0169

Combining with the J2 Modification

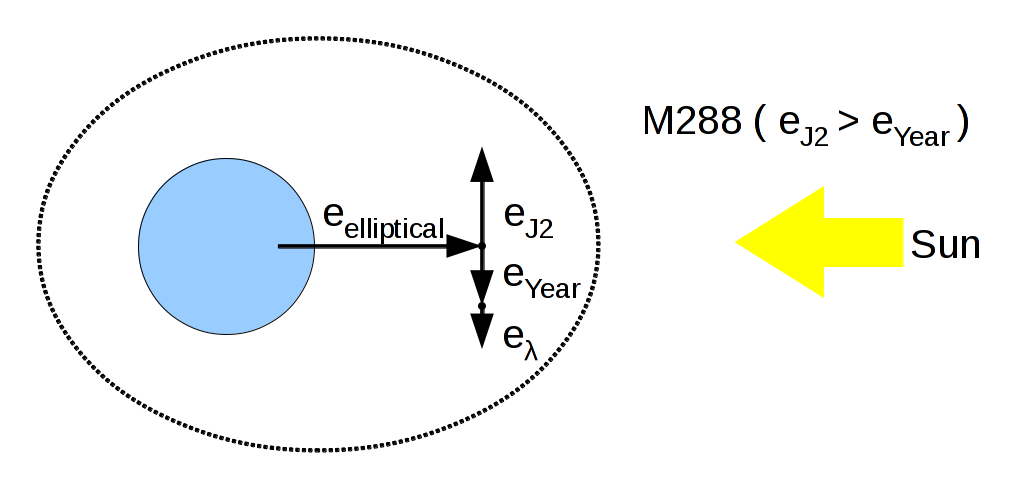

The simplest case for M288 is an eccentricity vector diagram like so:

For a bounded elliptical M288 orbit, e_{J2} = 1.771 \times e and e_{ year } = e , so with apogee towards the sun, e_{ \lambda } = 0.771 \times e . That means that for a 44μm 8.333 m2/kg thinsat, e = 0.0169 / 0.771 or 0.022, or perhaps a little larger because of the twice-annual variation in tangential light acceleration. Assume that the distance to orbits near M288 (for example, LAGEOS at 12331 km apogee) should be at least 0.022*12789 km = 280km, so there should be no valuable equatorial crossers between 12509 and 13069 km .

M360 orbits (The O3b satellites) have a J2 excess of 0.157 instead of 0.771, which means that the eccentricity to mass ratio will be almost 5 times larger than M288. M360 does not look like a practical orbit for low mass thinsats. Cheap launch and ballast will change this.

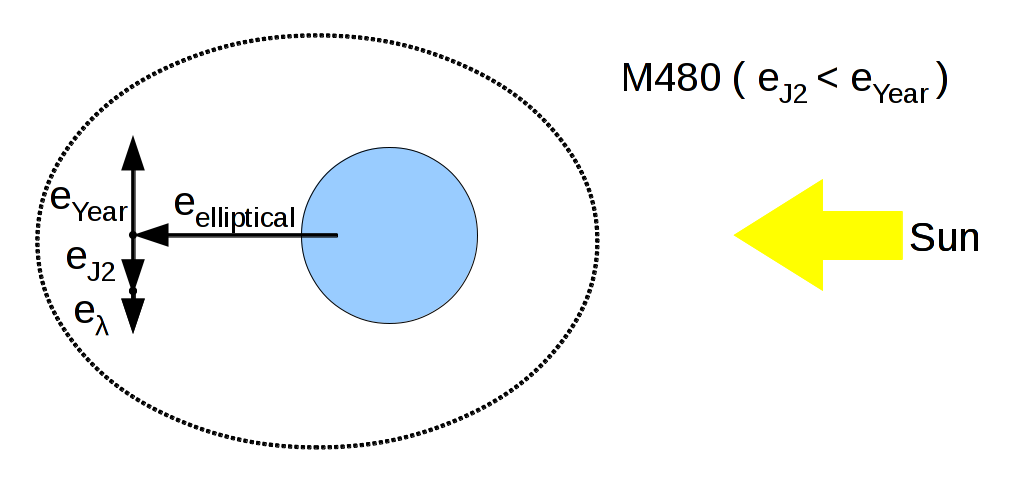

The M480 orbit ( 16756km ) is slower so e_{\lambda} is larger:

e_{\lambda488} = { \Large { { 3 M P \sigma Y } \over { 4 \pi V } } = { { 3 ~ \times ~ 0.33 ~ \times ~ 4.56E-6 ~ \times ~ 8.333 ~ \times ~ 3.156e7 } \over { 4 \pi ~ \times ~ 4877.51 } } } ~ ~ ~ = 0.0196 .

For a bounded elliptical M480 orbit, e_{J2} = 0.688 \times e and e_{ year } = e ~ ~ ~ , so with perigee towards the sun, e_{ \lambda } = 0.312 \times e ~ ~ ~ . That means that for a 44μm 8.333 m2/kg thinsat, e ~ = 0.0198 / 0.312 or 0.0633 . Assume that the distance to orbits near M480 should be at least 0.0633*16756 km = 871 km, so there should be no valuable equatorial crossers between 15885 and 17627 km .

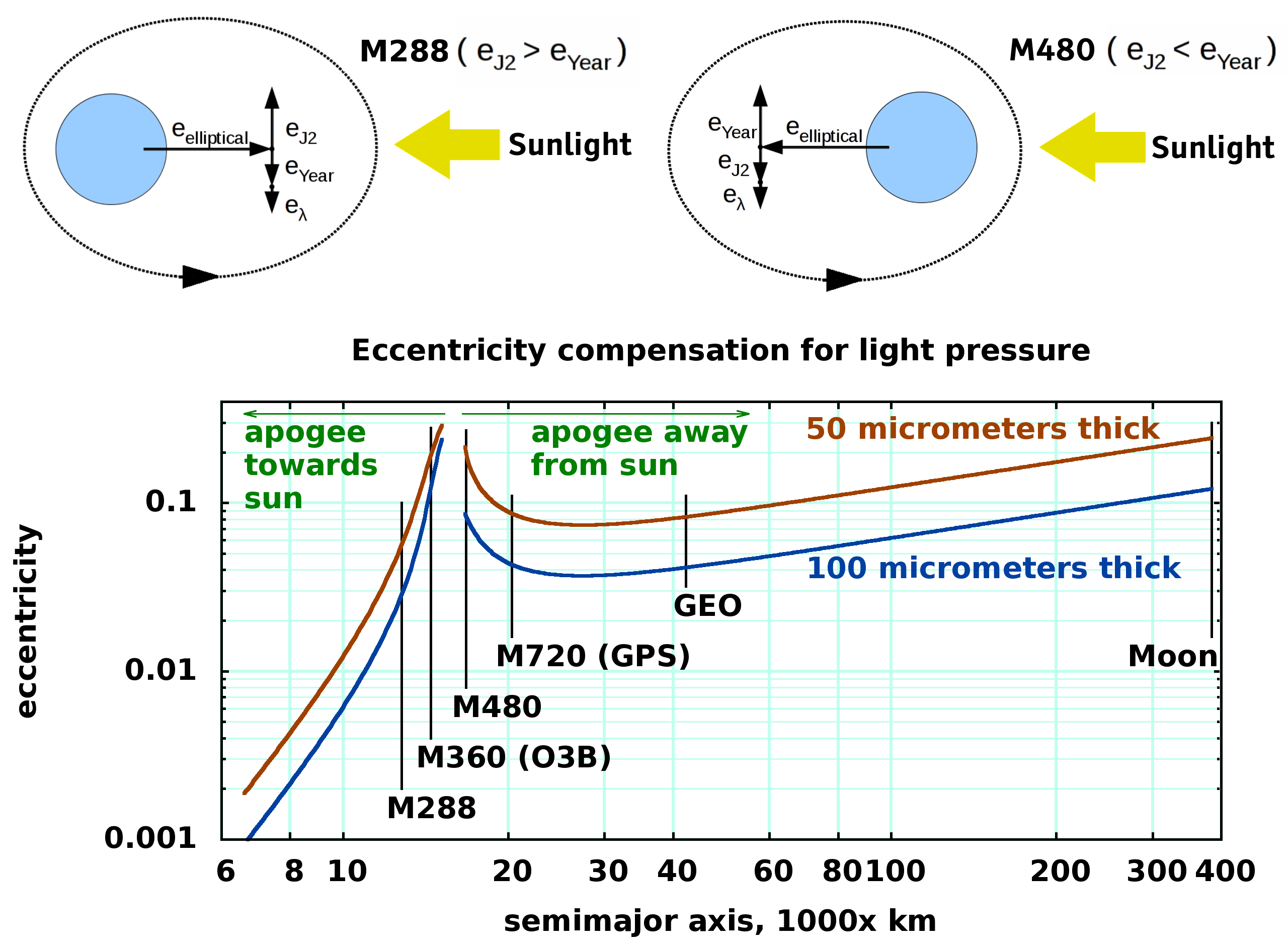

http://server-sky.com/LightOrbit#Eccentric

http://server-sky.com/LightOrbit#AlDens

Note added 2021 September 26: Thickesses are equivalent mass of aluminum; 100 micrometers of 2700 kg/m³ aluminum is 270 grams/m² or 27 mg/cm². This might be implemented as a very thin foil with tiny lensed solar cells and thicker-lensed computation chips. The lens globs can focus sunlight while dispersing some of the high energy radiation. Electronics should be redundant and error-correcting. Note that a VAST amount of computation and memory can be crammed into a submillimeter silicon die using a deep-submicron process and radiation-insensitive "leaky" gate oxides.

Note also an asymptote in the graph, between M360 and M480. Orbits are destabilized by light pressure in this zone. It is interesting and perhaps scientifically important that this radius is near the radius of the gap between the inner ( electron/proton plasma) and outer (electron) van Allen belts.

Inclination - Flattened Toroidal Orbit

Because of the eccentricity, we will incline the orbit, so that the central orbit can be set aside for heavier objects. We should consider a flattened torus so that this orbit does not go too far south or north. If we make the inclination for the M288 orbit ( e ~~~ = 0.0 ) 0.5°, then the orbit passes above and below the 12789 km central orbit by 112 km, compared to the 280 km sideways distance. The circular orbital speed at M288 is V = 5583 m/s. The relative velocity of the two orbits at crossing ( r = A, \cos( \theta ) = - e ~ ~ = 0.022, or \theta ~ ~ = 91.26° ) is:

tangential |

e V \cos( \theta ) = e^2 V |

2.7 m/s |

radial |

e V \sin( \theta ) |

122.5 m/s |

total |

e V |

122.5 m/s |

The "velocity shear" across the orbit is ( 122.5 m/s / 112km ) 1.09 m/s per km or 1.09e-3 / second. If we imagine a series of increasing-weight thinsats around the central orbit, lighter at the edges and denser near the central orbit, then M288 orbits that differ in velocity by 1 m/s will always more than 910 meters apart.

The locus of all these orbits will be a "double Möbius" strip (one full turn), with one edge along the circular central orbit and the other edge wrapping around it toroidally.

A note about thinsats and Space Based Solar Power in GEO

The J2 oblateness effect is almost nonexistent in GEO. The discussion by Soop above is focused on GEO satellites, which must be well positioned with very small errors in North/South and East/West position. The North/South position is strongly perturbed by tidal effects from the Sun and Moon, while the East/West position is perturbed by higher order nonuniformities in the longitudinal gravity field. These nonuniformities want to drag satellites towards 75°E and 105°W, while light pressure effects want to drive the orbit elliptical as above.

GEO is prime real estate; almost every orbital slot has an expensive satellite in it, and satellites are typically constrained to stay in an east/west dead band of about 0.1° so they do not encroach on their neighbors. Further, GEO comsats usually talk to fixed high gain dishes on the ground, with narrow beam angles, so they are constrained to 0.1° of drift in all directions. Server sky ground antennas are assumed to be steerable, so they are free to drift somewhat to the north and south. But they must be constrained east/west .

The total station keeping thruster budget for a GEO satellite averages 50 m/s per year or 1.6 μm/s2. With a conventional satellite dry weight of 1.5 tonnes, the station keeping requires an average of 2.4 mN. Traditional satellites use solar panels massing about 500kg/10kW (WAG), and assuming 20% efficiency ( 270w/m2 WAG) these 40m2 satellites are subject to 180 μN of sunlight force, or 0.12 μm/s2 of acceleration, smaller than the station keeping force.

Solar power satellites are intended to produce 1 kW per kilogram, which increases the forces needed for sunlight station keeping to perhaps 2.0 μm/s2, or 110 m/s/year .

If we do not correct the sunlight forces, then e_{\lambda-GEO} = { { 3 \lambda Y } \over { 4 \pi V } } = { { 3 \times 2e-6 \times 3.156e7 } \over { 4\times\pi\times 3074.6 } } = 5e-3 . The daily east/west drift would be about ±0.01 radians or 0.57° - clearly unacceptable in the tightly constrained GEO orbit. The mass must be increased to 6kg/kW, and thinsats would require similar mass to area ratios.

Although SSPS in GEO is "always on", it may be as much as 6 times heavier and 13.3 times harder to launch than thinsats to M480 - even with thinsats at 30% utilization to one ground rectenna, the launch cost per Watt is 4x cheaper. M480 thinsats are also 2.5x closer, and antenna sizes can be 6x smaller. If the rectennas are 6x cheaper, then we can deploy 6 for the cost of 1 GEO rectenna, and sell all the power from the thinsats, all around the world, bringing utilization closer to 100%.

Note that in the real world of grid power, demand is not constant over a day, and peaking sources are expensive. If SBSP can supply peak load, by switching the beam to rectennas in other time zones, the power becomes much more valuable. Overall, SBSP supplied with MEO thinsats can be up to 20x more profitable than power supplied from GEO satellites. In addition, because the arrays can be in inclined orbits, we the rectenna elevation angles can be reduced, and the power beams are less likely to interfere with signal beams from GEO communication satellites.

Lagrange Orbits and Light Pressure

Because of the biological effects of nocturnal illumination, both MEO and GEO SBSP deployment will be limited anyway. It is better to deploy large scale SBSP at the Lunar Lagrange points, where lunar perturbations and solar perturbations can be balanced with much lighter thinsats in very large arrays, perhaps with significant north/south inclination to the lunar orbital plane.